When I posted earlier about where the New Testament had come from, I condensed what is a massive, technical discussion about our material sources for the text. Right now, I’m producing a synopsis of the Four Gospels using the King James Version for use in my weekly religion class on the life of Jesus (see the bonus attachment below for an updated PDF). I keep finding at the granular level of most pericopes this question of where these stories originated. How did we come by these sayings of Jesus? How did principal observers communicate their experiences? How did those communications evolve into this text we read? I want to consider those questions here in a tad more detail than previously.

Provenance of the KJV in a Nutshell

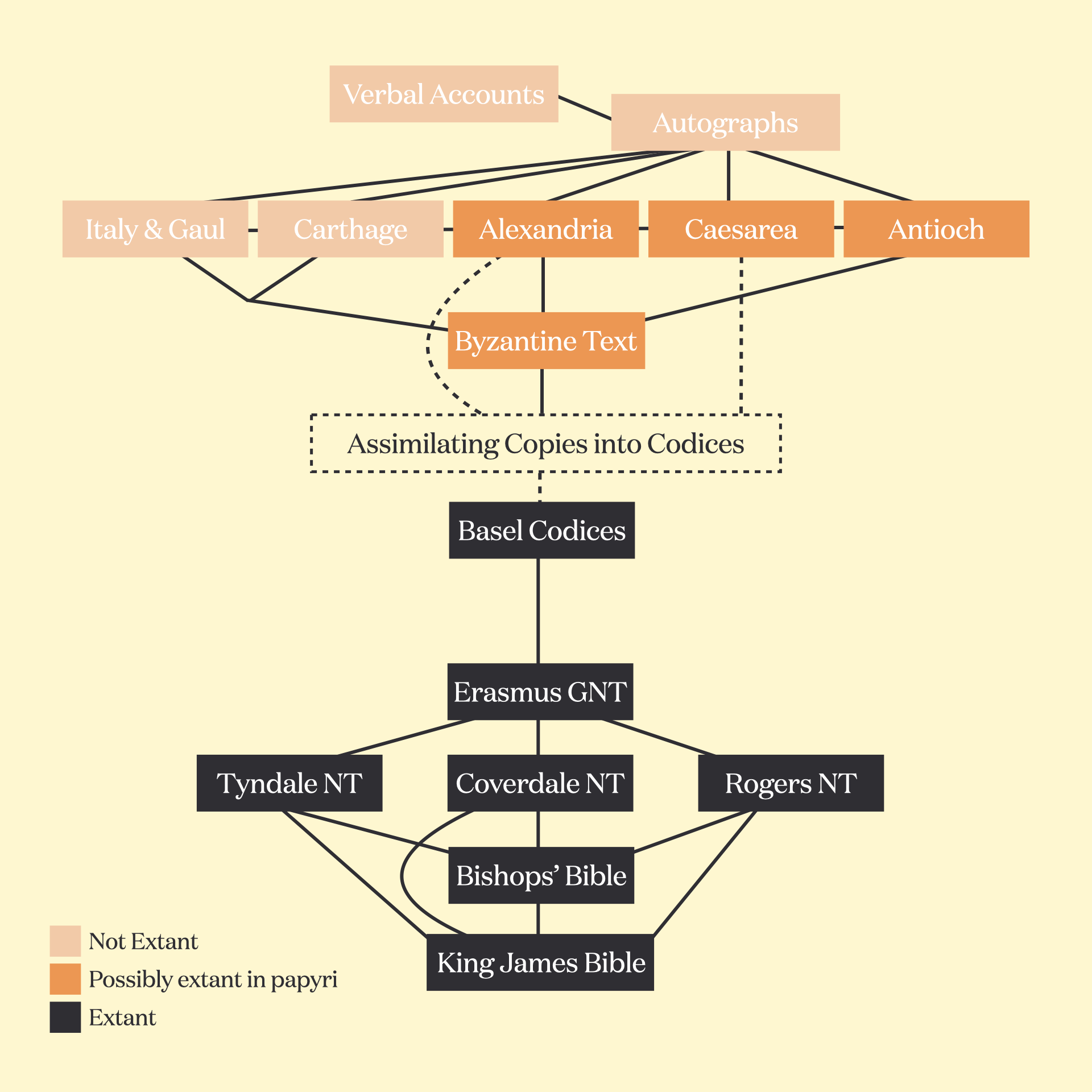

My earlier post traced the provenance of the King James New Testament backward this way:

Standard 2013 LDS edition of the Holy Bible revised spellings, punctuation, and typographical errors in the 1979 edition

Standard 1979 LDS edition of the Holy Bible was based on the 1769 Oxford edition of the King James Version

1769 Oxford edition corrected irregular punctuation and spelling in various printings of the 1611 King James Version

1611 King James Version used the second edition of the Bishops’ Bible as base text; pulled other variants from English Bibles produced by William Tyndale, Miles Coverdale, and John Rogers

All English Bibles used for the 1611 King James Version were translated from the 1516 Greek New Testament by Desiderius Erasmus

1516 Greek New Testament was based on seven manuscripts:

Miniscule 1(eap) — Codex Basilensis A.N.IV.2 (from 1100s)

Miniscule 2814 — Augsburg University Codex I.1.4.1 (from 1100s)

Miniscule 2(e) — Codex Basiliensis A.N.IV.1 (from 1100s)

Miniscule 2815 — Codex Basiliensis A.N.IV.4 (from 1100s)

Miniscule 2816 — Codex Basiliensis A.N.IV.5 (from 1400s)

Miniscule 2817 — Basel University Codex A.N.III.11 (from 1100s)

Miniscule 817 — Basel University Codex A.N.III.15 (from 1400s)

This is where the transmission of the text through material sources goes cold. We can’t peel back farther than those seven codices (called miniscules because of their lettering style), unless we reason through probabilities. It’s that kind of analytical reasoning that we call textual criticism. The story becomes really interesting.

Comparison of Texts

Setting aside the King James text, we could arrive at a different New Testament based on an earlier set of primary sources, ones that are closer to the original sources of the text. In theory, we could just look for any and all of the earliest manuscripts and assemble their text by comparing them. This would mean tracking every lemma—the basic word unit of each text—and every variant across manuscripts. For those lemmata that don’t have any variance, we’d accept that word as valid. For those with high variance, we’d put a pause button on accepting those into the main assembly of words. For those with mild-to-moderate variance, we’d also put a pause on those, but have good reason to accept the majority version.

That’s a simple description of what textual critics do, except they’re pulling together any piece of data that can explain text and textual transmission. Detective work, totally.

Here’s what decades of this kind of research has turned up: the Byzantine Text.

Why Byzantium Matters Here

In 303 CE, Emperor Diocletian pronounced Christians criminals unless they participated in Roman sacrificial rituals to the gods. Libraries across the Mediterranean that had collected Christian writings became targets of arson. We know of major libraries in Alexandria (in North Africa), Antioch (in Syria), Caesarea (in Judaea), Italia, Gaul, and Carthage (in North Africa) that were raided and their Christian contents destroyed. Galerius followed Diocletian two years later and continued the imperial persecution until 311.

But something counterbalanced this persecution—Constantine, whose mother was a Christian, ascended to Caesar status in the eastern half of the empire, what would become Byzantium. And at his new capital city far from the old capital of Rome, Constantinople, those Christians safely collected writings lost elsewhere. It’s for this reason that most of the earliest manuscripts of the New Testament are Byzantine.

The farther east one goes in the 4th century toward Constantinople, the more Christian material one turns up. Comparing manuscripts and tracking variants lead to some consensus notions of the earliest New Testament text: the majority of consistent lemmata across the manuscripts are Byzantine, and so this so-called Byzantine Text is often a baseline for comparing the later (as in medieval and Renaissance) manuscripts. For other reasons, the Byzantine Text isn’t the only source that might be considered authoritative for the earliest versions—after all, quite a bit of manuscripts remain to be deciphered (more on that in a second). But speaking in probabilities, our current best bet is on well-established Byzantine texts to approximate what the earliest versions of the New Testament said.

Recovering Papyri and Codices

Archaeologists in 1896 excavated an ancient rubbish heap in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, and discovered scores of papyri and papyrus fragments. Papyri everywhere—stuffed in discarded shoes, in pots, all over the place. The scale of the Oxyrhynchus excavation was so large, scholars had scarcely begun trying to piece together the artifacts by the time James E. Talmage wrote Jesus the Christ in the early 1900s and 1910s. By 2021, over half a million papyrus fragments remained to be deciphered; so far, less than 2% have been deciphered and catalogued. Scholars at BYU actually helped to accelerate this project: they developed a multispectral imaging method for enhancing the faded text on extremely brittle papyrus and also pioneered a plant-DNA analysis method to stitch fragments together. But these methods only came online in 2005(!), so we’re a long way from knowing what all exists in the Oxyrhynchus cache. Already the list is massive, containing far more works than just the New Testament.

In 1931, an antiquities collector, Chester Beatty, acquired a sizeable cache of papyri containing biblical texts. Because he trafficked in the illegal antiquities market, the provenance of all the materials in the Beatty collection is uncertain, though the materials have been authenticated several different ways as 3rd-century and later papyri. Later in the 1950s, another collector named Martin Bodmer identified many other papyrus fragments. Together the Oxyrhynchus, Beatty, and Bodmer collections represent the most sizeable supply of earliest New Testament manuscripts yet discovered. Only by the late 20th century have scholars even had access to manuscripts dated to the 3rd century and earlier—and digitization has accelerated our access and knowledge of their contents in only very recent years and remains an ongoing concern. We should expect to learn things in coming years that could greatly revise what we have said about the Four Gospels.

The Textual Pedigree

This graphic charts out the textual pedigree between the original verbal accounts of principal observers, the autographs (or the accounts’ first written form), the papyri reproductions of the autographs, codex reproductions of papyri texts, and finally translations into English. Consider this: the chapter format was not introduced to the text until Erasmus’s Greek New Testament was aligned with the Latin Vulgate chapters in the early 1500s—1,400 years after the first autographs were composed. Verses came later. So, the divisions we’re so used to are as foreign to the text as our English translation.

If we’re on the hunt for the text of the Four Gospels—as the original tellers and writers intended it—then we have the exciting prospect of digging for it in the ongoing papyri research. We don’t have to rely only on reconstructions of the Byzantine Text or on later codex reproductions of lost papyri. When we do this kind of reading, we discover how the amazing, enduring process of preserving the Four Gospels came with its own cost in interpolations, mistranslations, and other changes to the way their stories read. Our image of Jesus will—hopefully, likely—refine.

Sources

- Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 2nd ed., translated by Erroll F. Rhodes (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1987).

- Harry Y. Gamble, Books and Readers in the Early Church: A History of Early Christian Texts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

- Bruce M. Metzger and Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 4th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Larry W. Hurtado, The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2006).

- D. C. Parker, An Introduction to the New Testament Manuscripts and Their Texts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

- James R. Royse, Scribal Habits in Early Greek New Testament Papyri (Leiden: Brill, 2008).

- Arthur G. Patzia, The Making of the New Testament: Origin, Collection, Text, and Canon, 2nd ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2011).

- Brent Nongbri, God’s Library: The Archaeology of the Earliest Christian Manuscripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018).

Bonus Attachment

I’m making progress on my Synopsis of the Four Gospels in the King James Version for Latter-day Saint readers. Here’s the latest that brings it all the way to Pericope 114. I’ve enhanced it with red-letter text for any dialogue attributed to Jesus and updated footnotes with any noteworthy differences between the text and manuscript versions. I hope you enjoy: