Improving Our Interpretation of the First Vision

Since the first edition of the Pearl of Great Price was published in 1851, its account of Joseph Smith’s 1820 vision became the most popular of the nine contemporaneous accounts produced in his lifetime. We’ve been raised on this telling, rendered in JS’s own voice and framed as an official response to the secondhand reports circulating in the United States in the late 1830s. Whole pageantry has developed around the “Joseph Smith — History” (or JS History) account, enough to sustain a historical study of its own.[1] This pageantry has produced outdoor theatre, films, and artworks, to say nothing of the millions of individual recitations and testimonials Latter-day Saints have presented in devotional meetings. Somewhere, some missionary right now is reciting the words from JS History about two personages appearing within a pillar of light in a shaded grove of trees, and that missionary and that missionary’s audience are imagining something probably closer to mythology than history.

I’ve made several studies of the First Vision over the years. This year being the 200th anniversary since the vision, I had wanted to sketch out some research but time has eluded me. (Ah, pandemic, thank you.) If I were invited to discuss the First Vision with a curious audience, I’d want to share some facts about the primary sources and a more accurate setting to visualize when we commemorate the vision.

Sources

The Joseph Smith Papers has the best breakdown of primary sources for the First Vision anywhere. Seriously, you should check it out: Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision. There are nine total primary accounts, four of which are firsthand from JS’s own production and five that are secondhand from contemporaries. Arranged in their order of production, here they are (with my shorthand titles in parentheses, for later reference):

Firsthand Accounts

- JS History, ca. Summer 1832 (1832 History)

- JS, Journal, 9–11 Nov. 1835 (1835 Journal)

- JS History, 1838–1856, vol. A-1 (1838 History)

- JS, “Church History,” Times and Seasons, 1 Mar. 1842 (Times and Seasons Account)

Secondhand Accounts

- Orson Pratt, [An] Interesting Account, 1840 (Pratt Report)

- Orson Hyde, Ein Ruf aus der Wüste, 1842 (Hyde Report)

- Levi Richards, Journal, 11 Jun. 1843 (Richards Journal)

- David Nye White, Interview of JS, 21 Aug. 1843 (White Interview)

- Alexander Neibaur, Journal, 24 May 1844 (Neibaur Journal)

And there you have it: a finite set from which we can hear from JS about his 1820 vision. Each source has its own issues of provenance, context, and reception history; I won’t dive into these issues and instead point you to Harper’s 2019 study, First Vision, in case you’re interested in a thorough discussion of each source. Instead, I just want to point out some important elements of JS’s narrative that tend to get left out as readers center on the 1838 History alone.

Elements of the Event

Historians have compared these accounts in great detail. Probably the most accessible and yet detailed summary is James Allen and John Welch’s Opening the Heavens article, which I recommend as a preliminary approach to reading the accounts together.[2] This is just one synthesis of the nine sources, however, and Allen and Welch avoid any deep contextualization. To get a quick review of the main elements present in all the accounts together, consult the article’s several tables, which list the narrative elements and mark which accounts attest them. Since we are generally so familiar with the 1838 History version, I’ll just point out those elements attested outside the 1838 account:

- JS’s age may have been 15 at time of vision

- JS wanted to “get religion” like he saw others do at revival meetings

- JS worried about his future and the state of his soul

- JS sought forgiveness of sin

- JS felt a deep concern for humankind

- JS looked for a church built up as in the New Testament

- JS was convinced God was good and majestic

- JS wanted positive evidence, not accept dogma of churches

- JS didn’t just pray, but prayed “mightily”

- JS cried for mercy

- JS heard footsteps while praying in the grove

- JS was beset by doubts and strange images

- JS felt easier between an onset of darkness and the appearance of light

- JS saw a pillar of fire with flame that rested on trees but did not consume the leaves

- JS saw light all around him

- JS saw one personage appear first, then another

- JS thought both personages resembled each other exactly

- JS saw many angels

- JS’s sins were forgiven

- Jesus identified himself

- JS told not to join the Methodists

- JS told no church did good, that all were in sin, and all had broken the everlasting covenant

- JS told no church was acknowledged by Jesus as Jesus’s church

- Jesus expressed anger at the state of wickedness in the world

- Jesus promised the fullness of the gospel would be revealed to JS

- JS felt feeble after the vision

- JS filled with love, joy, calm, comfort, and peace afterward

No doubt, the other accounts amplify what appears in the 1838 History. It’s certainly worth reading all these accounts when studying the First Vision.

Prevailing Notions

Even after the Joseph Smith Papers has done such a great job of alerting members of the church to the broader evidence of the First Vision, we still see some notions persist. The big ones:

- That the current site of the Sacred Grove is where JS prayed in 1820.

- That the setting of the vision was a lively spring morning.

- That JS experienced an external visitation of God the Father and Jesus Christ.

Perhaps these amount to harmless subjectivities and I’m just ranting on my personal pet peeves. But when our missionaries present a literal setting as the literal place of a divine encounter that amounts to a world-order cosmic event, it becomes something of a potential liability when converts and members visit the First Vision accounts and wonder about inconsistencies. I’m personally OK with walking the modern trails through the Sacred Grove and contemplating the whole Smith homestead as the radius where extraordinary visions occurred—but this mentality came after confronting the inconsistencies in the First Vision pageantry and opening myself up to the historical likelihoods. I believe it aids faith and testimony to critique our collective pageantry and folklore, and a worthy critique will provide evidence and factual detail. So, here goes.

Original Site of the Sacred Grove

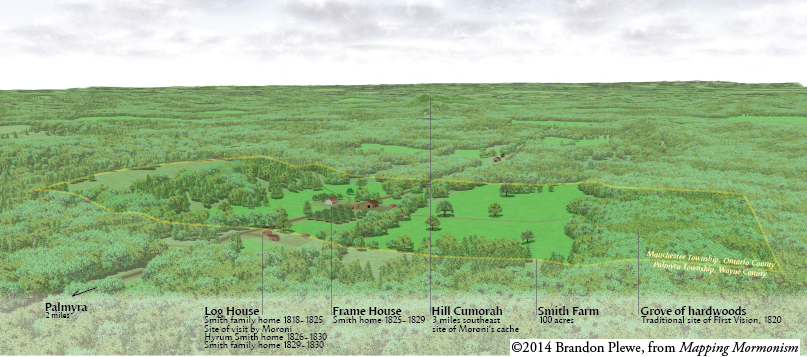

We need to get some geography settled before diving into where JS prayed in early spring 1820. The best graphic, I think, is from the Mapping Mormonism atlas:

This view of the Smith homestead faces south with the Hill Cumorah in the background. The “Grove of hardwoods” on the right is known as the west grove, or the west end of the farm. (This is important for interpreting some historical sources that describe the acreage when the church purchased the land in 1907.) A couple of things are important to point out: notice how the eastern/left acreage slopes higher than the plot by the road, log house, and frame house. The Palmyra Temple presently sits on this upper slope overlooking the flatter land to the west/right.

The way the Smiths came to farm the 100-acre plot of land is complicated and convoluted, and reads much like the contingency language filling mortgage contracts. Put simply, the Smiths lived in Palmyra for about 18 months before building a log house immediately adjacent to the property line where they were trying to purchase land. They moved into the log house probably sometime in 1818 and no later than 1819; a land agent was appointed in June 1820 for the 100-acre Nicholas Evertson property that the Smiths wanted to buy; and in July 1820, Joseph Smith Sr. signed a contract for the Evertson property. The time JS identified as when his vision took place becomes something of a historical debate — it’s possible JS really was 15 years of age and experienced his vision in 1821, which would line up better with the timing of the acquisition of the 100-acre farmland. (Some critics have pushed the 1821 date as evidence of JS hedging on his story or getting crucial details wrong, thus undercutting JS’s visionary claims.) But the timing of camp-meeting revivals in the area, a detail JS is quite consistent about, favors 1819–1820. (Within a 20-mile radius of the Smith log house, more than 25 revival meetings occurred between 1816 and 1821; any of these, including the large 1819 Methodist Conference, JS could have easily attended, and we know the Smith family sold wares at such events in 1816 and 1817, so he may have been to several such gatherings.)

This timing matters for dating the vision, sure, but more importantly I think, for locating where JS would have had the vision. JS said he went to “the woods where my father had a clearing” and “went to the stump where I had stuck my axe when I had quit work” (White Interview). These details suggest JS remembered the principal setting as when his family was actively clearing land for farming — and if the vision occurred in early spring 1820, then this must have been at the very earliest possible stage that the Smith family could have begun clearing land by a handshake agreement with the Evertson estate. The sequence in which the Smiths or anyone else at the time cleared deciduous-forested land for cultivation moved from higher ground to lower ground for a few very good reasons.

First, winter was a prime time for cutting and hauling such large trees. Deciduous trees hold less sap in winter making them easier to cut and lighter to haul. Where the Smiths lived, asheries purchased burned remains of large log fires to make potash. A typical one-man operation cleared about 10 acres in a year; torching the wood for ash could yield a faster clearing, but not much more than 15 acres. Lucy Mack Smith said the Smiths cleared something like 30 acres their first year — meaning, if the White interview is accurate, JS went to the clearing, not the forest, and this clearing would be where the family intended to plow ground and cultivate a field.

The one spot where neither the Smiths nor the later landowners cleared is the western grove of trees — the place where visitors walk trails and are told JS had his 1820 vision. Simply integrating the primary sources and reading them in their original context rules out the western grove as the site.

Take a look at the graphic again and notice two spots on the east side of the property that were cleared: the highest patch near the left-most property line and the next path below the slope east adjacent to the frame house. This is consistent with surveying of the property that found these clearings were human-made, very likely part of the 30 acres the Smiths cleared first. Now, this bit of evidence is somewhat circumstantial because we don’t have a direct source telling us where the Smiths started clearing land, so we’re now in the realm of probability, not fact. But we know that farmers at the time commonly began their clearing at highest points of elevation and worked their way down for a few reasons: (1) it was easier to haul timber down-slope; (2) they preferred a flat surface for burning timber for ash; (3) they wanted to start a harvestable crop as quickly as possible and would want a flat surface for sowing a field; and (4) sawing wide trunks is murder on your back and cutting trees every day on an incline is typically something they preferred to do last. If the Smiths cleared land in the order of highest-to-lowest elevation, then the 30 acres would have included the upper and lower patches between the east property line and Stafford Road plus some orchard and garden plots around the later frame house and cooper shed.

Revisiting the White interview account, this source provides the most detail about specifically where JS went to pray: the “woods where my father had a clearing” makes sense as a patch within forested surroundings where they were in process of clearing land. We should imagine, then, plenty of trees in the background but JS kneeling on leafy dirt with tree stumps all around and nearby. White also has JS saying that he “went to the stump where I had stuck my axe when I had quit work.” This seems quite specific: JS kneeling and perhaps resting on a tree stump. If this is where he had quit work, we should expect a felled tree that had not yet been hauled and burned, as well as other large full-sized felled trees in the clearing. Because the Smiths continued to clear the patch of grove where JS prayed in 1820, this means today there won’t be that surrounding forest, there won’t be tree stumps in a clearing, and there won’t be a canopy of unfelled trees. There are a couple of likely places to visit that won’t be like the grove of hardwoods in the western edge of the farm — an open field near the frame house or inside the temple that now stands on the upper clearing. (Or the temple parking lot.)

Why the Western Grove Gets Attention

The historical record can account for why the church devoted attention and resources to preserving the western grove of the Smith homestead. Put simply, when Joseph F. Smith negotiated the church’s purchase of the land in 1907, he said the owners at the time said a previous owner had said that JS had said his vision had occurred in the western grove. When we track down the claim, it gets a little dicey. Apparently William Avery Chapman said in 1913 at the close of the land sale that his father Seth T. Chapman had said after 1860 that Seth had heard his childhood friend JS tell of the vision, and so the Chapman family left 10 acres of the western edge untouched. The source is a 1934 John Wells reminiscence of an interview Wells had with William Avery Chapman in 1913, the copy of which is in the private possession of Don Enders. Mapping out the provenance, then, means we have to believe in a fourth-hand claim made over a hundred years after JS’s family left their farm. This comes nowhere near my standard of proof and categorically meets the definition of folklore. I have questions, too, for the Chapman reminiscences. For one thing, how can we be sure the Chapmans, who weren’t devotees of JS by any measure, weren’t endeavoring to drive up the value of the property by making claims about the First Vision? When the best we have is trusting William Chapman’s word that his father Seth really did converse with JS before 1830 about the First Vision, I’d say this leaves plenty of room to be suspicious of either Seth or William’s motives. At best, they’re still unreliable narrators.

And yet—I’m glad those 10 acres of untouched forest remain. Had they cleared all the land on the property, we would probably today be trying to regrow the forest like the church is doing with the Hill Cumorah. It’s a stunning place absolutely worth attracting visitors.

Other Prevailing Notions

In the next posts, I’ll explore the notions that JS went into the Sacred Grove on a lively spring morning and that his vision was an external visitation of God and Jesus.

- See Steven C. Harper, First Vision: Memory and Mormon Origins (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).↩︎

- James B. Allen and John W. Welch, “The Appearance of the Father and the Son to Joseph Smith in 1820” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, 1820–1844, edited by John W. Welch, 2nd ed. (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 2017), 35–75.↩︎