If we look deeply at the Gospel of John, we’ll find several places where this gospel more than others posits an identity for Jesus that breaks from prior Jewish expectations. In other words, we see the development of ideas about Jesus and who he represented—was he a prophet? a mystic? a miracle-worker? a wise Rabbi? a philosopher? a great high priest? the Son of Man? the Messiah? the Son of God? The Gospel of John takes up this question head on in its prologue and then takes occasion to drive the point home. Jesus was all of those things, and more—Jesus was God, that’s the huge, major contention the gospel makes against certain antagonists of its time that criticized Christians for worshiping an executed criminal.

Right after the disciples landed in Gennesaret village, the people there recognized Jesus and brought their sick and diseased to be healed, “and besought him that they might touch if it were but the border of his garment,” and as many as touched him were healed. John has this interesting digression: others from nearby villages had expected to see Jesus and when he hadn’t arrived, they sought him out. Finding him, they asked him when he had come to this place instead. This sparked a monumental reply.

Jesus answered with: “Ye seek me, not because ye saw the miracles, but because ye did eat of the loaves, and were filled.” His exchange with this audience became the Bread of Life Discourse, one of the extended discussions in the Gospel of John about Jesus’s identity and life mission. Jesus had pointed out the true reason for these people tracking him around the lake: they had been in Tiberias/Magdala the day before and were in the crowd that had eaten of miraculously multiplied food until they were stuffed, and rather than resonate with Jesus’s preaching, they now wanted the meal again.

Some Important Context

I want to pause and point out an important piece of context about the Gospel of John and this pericope. One of the precursors to this particular gospel being written was a widespread polemic (meaning, antagonistic argument) that had surfaced throughout the greater Mediterranean against Christianity. It particular, Roman elites spurned this new Christian movement for a number of reasons, but among their worst complaints was that Jesus’s followers were cannibalistic—these people gathered each week to eat the flesh of their lord and drink his blood. Just as folks commonly misattribute polygamy to today’s Mormons, in the second century it was said broadly that Christians performed a cannibalistic ritual.

John’s narrative presents a clear and deep discussion about the Bread of Life and what Jesus meant when he invited his disciples to eat and drink of his body and blood. This discourse articulates a powerful relationship between us and Jesus and God, an essential teaching that may often pass us by. Or, probably more often than not, we cloud our interpretation with esoteric symbolism when the teachings were quite plain to Jesus’s immediate audience.

Some Important Rhetorical Figures

In rhetorical studies, we have a couple of rhetorical figures that can help us interpret a passage. Here’s what I mean. If we take a passage and want to work out its meanings, we can look at the arrangement of words and phrases to discern their functions—this would be rhetorical analysis. And within rhetoric, people use language to express logic, symbolism, all sorts of things. The rhetorical figures, meaning the particular arrangement of phrases and ideas, can reveal what is being intended. I like Gideon O. Burton’s website, rhetoric.byu.edu, as a resource for learning and studying rhetoric. Burton also offers a great definition: rhetoric is a discipline for training students to perceive how landuage is at work orally and in writing and to become proficient in applying the resources of language in their own speaking and writing.

There are two related rhetorical figures that really matter for understanding Jesus’s discourse on the bread of life in John 6: the enthymeme (EN-thih-meem) and the sorites (so-RYE-teez). An enthymeme is when the figure of speech gives a conclusion coupled with a reason. For example: Knives are sharp, so you should curl your fingers away from the blade when using one. This presents an enthymeme because the statement indicates something conclusive and then connects a reason to it. You can spot the enthymeme style in this example by the word so. (Given that) knives are sharp, so (therefore) you should curl your fingers away from the blade. Words like “therefore,” “thus,” “because,” “for,” “wherefore” all can indicate an enthymeme.

The sorites figure is quite simple: it is just a chain of enthymemes.

Jesus displayed a command for rhetoric across his ministry. We read him spin up the parable better than any other historical figure. He also uses antithesis in the Sermon on the Mount (“You have heard it said/but I say to you”). He employs hyperbole (“It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God”). He uses imitation, casting a teaching in the same poetic and rhetorical stylings as the Torah or as Isaiah or Jeremiah. And on and on. In this discourse on the bread of life, Jesus drops a sorites for the ages—a chain of enthymemes all about why to follow Jesus and how to receive him.

Why to Follow Jesus and How to Receive Him

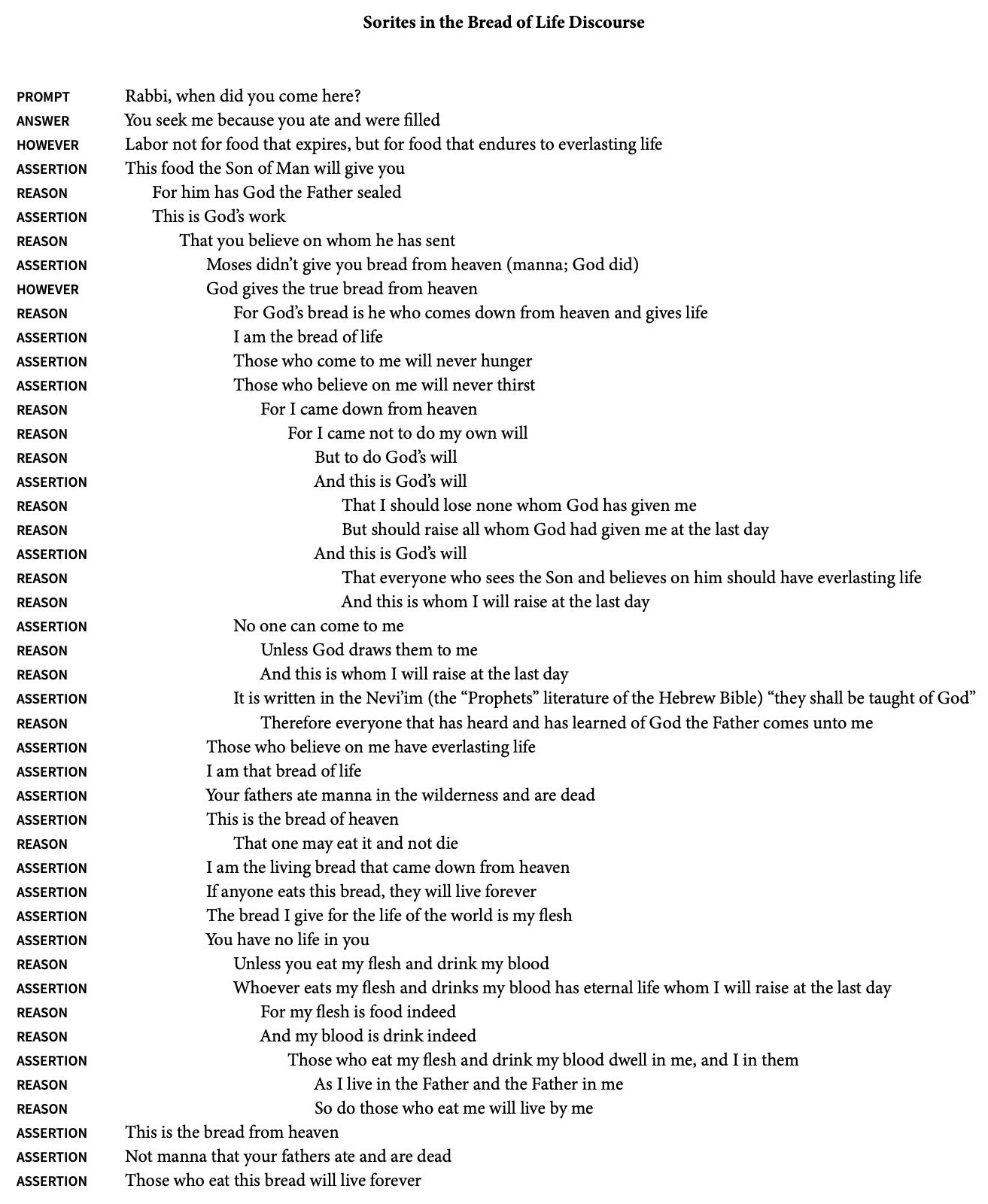

Let’s examine the sorites of this discourse and see what that tells us. For simplicity, I’ll leave out parts where Jesus’s audience interjects with questions. The reasoning all coheres anyhow. First, notice that an enthymeme moves from an assertion (X) to a reason (Y). In our previous example, the assertion was knives are sharp and this assertion goes undisputed, presented as clear fact, and presupposes agreement—we all recognize knives are sharp. The reason here is the novel idea of the enthymeme, the logical piece. Given X, therefore Y. Knives are sharp, therefore, curl your fingers away from the blade. So, in this discourse, we’re noticing where Jesus asserts an idea and then gives a reason for the assertion. And then we’re paying attention to chaining, where the reason becomes another assertion or the basis for another assertion, and so on.

The graphic above is my attempt to break down the sorites sequence in the Bread of Life Discourse. From this, I think we can see the main line of presentation, the takeaways of Jesus’s teaching. First off, the figures of “living waters” and “bread of life” anchor the whole discussion. Semantically, the descriptors are the same, so for semantic consistency, we could refer to “living waters” and “living bread,” or “water of life” and “bread of life.” These metaphors have strong association with Old Testament elements: the living waters were understood to be rain, the kind of water that falls from the heavens (God provided rain to quench the thirst of the Israelites during their sojourn in the wilderness); and the living bread was understood to be manna, the bread that fell from the heavens like rain. Jesus drew on both of these images to say that those who come unto him will receive God’s true bread and God’s true water, bread that when eaten will never induce hunger and water when drunk will never induce thirst.

Now, the sorites figure chains together rationales of previous assertions. Given this/therefore that; given that/therefore this other thing; given this other thing/therefore another thing; and so on. Jesus built conclusions from these facts about the living water and living bread: one cannot come to Jesus unless the Father draws one to him; and one cannot be drawn by the Father unless one is taught by God; and one is taught by God when one hears and learns of the Father.

I believe the sorites chain converges on that all-important takeaway: expect to hear and learn of the Father. Jesus connected the pieces and drew out that conclusion—to hear and learn of the Father is to eat of the bread of life and drink of the living water.

Jesus took on the responsibility of declaring the Father. This he emphasized repeatedly, and not just here, but throughout his whole ministry. It then falls to us whether we’ll learn of the Father as Jesus has declared him.

Reactions

How did disciples react to this discourse? John continued: “many therefore of his disciples, when they had heard this, said, This is an hard saying; who can hear it?” When Jesus heard their murmurs, he asked, “Doth this offend you? … The words that I speak unto you, they are spirit, and they are life.” The words—again, the delivery of Jesus’s teaching of the Father, what we hear—these we must ingest and learn. If we can rely on them, really trust them, the pistis in Jesus’s invitation to us, then we will live by them and be raised up someday. But, “from that time, many of his disciples went back, and walked no more with him.”

What pulls us away from Jesus’s words about Heavenly Father? What illusions keep us from accepting the true version of God that Jesus revealed? How do we pigeon-hole the grandeur of the true God into our small assumptions or selfish ideals? The fact of the matter is, we only deprive ourselves of everlasting bread, it is we who keep ourselves hungry. Like some of those disciples, I want to ask Jesus, “Lord, evermore give us this bread.” Based on Jesus’s reply to them, I ought to look for Jesus’s words about God in Heaven and disabuse myself of my assumptions, trying continually to learn the truth of who God really is as revealed in and by Jesus.