At this point in the story, we’re in Galilee right in the middle of the Galilean phase of Jesus’s overall ministry. Jesus had started the ministry in the northern portion of the region and frequented villages that had synagogues. His paths took him around the lakeshore of Gennesaret until eventually he reached the southwestern area of Galilee—a more “provincial” setting where people from the Roman province of Judaea traveled and resided. We see Jesus’s message adapt to this (slightly) more cosmopolitan, or mixed, population. This audience consisted of Jews and non-Jews, agrarian farmers and fishers, hired day laborers and extended-family farmsteaders.

Jesus made a quick trip to Jerusalem for some unstated reason in pericope 118 (John 6:1), probably one of the annual feasts. But he returned to Galilee, presumably to that southwestern area he had left. The established roads between Jesus’s departure point for Jerusalem and the shortest path back suggest he could easily have returned back the way he came.

Death of John the Baptist

And then tragedy ensued. Herod Antipas, son of Herod the Great, had ordered the execution of John the Baptist. Some intrigue lies behind this execution we ought to work out. The dynasty of Herod the Great was, to put it mildly, a mess. Lots of royal sabotage (Herod the Great executed two of his own sons), lots of divorce and remarriage to create new political alliances, and the like. Herod the Great had multiple wives and many children with these wives. How this related to John works out like so: Herod the Great had three particular sons with different women: (1) Herod II, whose mother was Mariamne II; (2) Aristobulus IV, whose mother was Mariamne I; and (3) Herod Antipas, whose mother was Malthace the Samaritan. This means that Herod II, Aristobulus IV, and Herod Antipas were half-brothers to each other. Aristobulus’s daughter, Herodias, was arranged to marry Herod II by Herod the Great. (This means she was married to her half-uncle.) After Herod II’s death, Herod Antipas divorced his first wife and married Herodias, a rather obvious political maneuver (if you’re shrewd, and the Herodians were shrewd) to shore up his half-brother’s princedom for himself. It was this move that John the Baptist criticized for being against the Torah codes that stipulated whether and how a brother might marry his deceased brother’s wife and provide for her.

The gospels of Mark and Matthew say that Herod Antipas wasn’t too bothered by John. But his half-niece, the daughter of his new wife Herodias, danced for him in a ploy set up by Herodias to gain his favor. It worked. The half-niece’s dance so enamored Herod Antipas that he pledged to give her anything up to half his princedom. At this, the half-niece demanded the head of John the Baptist. Herod Antipas ordered the execution (perhaps relunctantly, based on the gospel accounts). John was beheaded in the prison where he had been held, and the executioner conveyed the severed head to Herodias’s daughter in a “charger,” an archaic translation of an Old French translation of the original Greek word pinax, which meant “platter.” What’s more: the pinax was the table element used to serve meat and was often decorated with glaze or painted images of animals, adding further grotesqueness to the story. This little detail might suggest that Herod Antipas displayed some contempt for Herodias and her daughter, as if to say, “You want the head of John? Well here it is, during your meal. Enjoy.”

Mark notes that John’s disciples came for John’s body and laid it in a tomb. Part of their Jewish—and certainly Essene—practice involved wrapping the head of the corpse with a separate cloth, applying fragrance and ointment to the body, and then wrapping the whole body in a shroud. We read about Lazarus being raised from the dead and exiting the tomb, and a “napkin” (soudarion, sudarium in Latin, the facecloth) having to be removed from his face (John 11:44). In this instance, John was entombed without the sudarium for obvious reasons, which leaves the possibility that this community of disciples treated John’s body as though it had been desecrated. We’ll see with Jesus’s entombment a similarity, a kind of mirroring in the narrative. Mary Madgalene will wonder where “they” (the Romans) had taken Jesus’s body after she will find the sepulcher empty, which will imply she thought the Roman’s won’t have finished with their death pageant and will have taken the body to further desecrate it. In a sense, John, again, here prepared the way before Jesus.

Sepulchers are mentioned in the four gospels only a few times: here at the death of John; also in the Gergesene/Gadarene region where the Legion exorcism occurred; at the death of Lazarus; and at the death of Jesus. Notice how the tombs always connote tragedy: John’s death, a grotesque display of Herodias’s and Herod Antipas’s callousness; the man afflicted with Legion breaking chains and frightening the whole countryside, dwelling among the tombs; Lazarus, sending the whole of Bethany into deep mourning. And what could be more horrific and dark and heavy than Jesus’s crucifixion and entombment? Notice, too, how these sepulchers are also depicted as sites of deliverance: the man afflicted with Legion amazed the countryside after he had been brought back to his “right mind”; Lazarus came forth; Jesus was resurrected and left behind an empty tomb. What about John’s tomb? We see in pericope no. 120 how the works and miracles of Jesus had Herod Antipas wondering whether John had arisen from the dead. So while we, as readers, assume John still lay entombed, narratively speaking, his tomb also represents not a final resting place, but something transient. John’s influence, his very spirit essence, wasn’t done yet.

I think all this is to say that the gospels seem to treat tombs as both/and, not either/or—they’re both tragic and miraculous, sites of death and life. We can see an especially Christian motif emerge in these stories, a motif that takes the figure of the tomb and transposes it away from only an image of death. Why? Because this is the beating heart of Christianity: Jesus is risen, and that matters for everyone.

Return of the Twelve

Prior to this episode, Jesus had commission twelve of his disciples to preach throughout the region, telling them to visit villages and not “go from house to house.” Pericope no. 121 indicates they returned from this tour reporting to Jesus, followed by Jesus inviting them “into a desert place” to “rest awhile.” Mark adds this detail: “for there were many coming and going, and they had no leisure so much as to eat.” In other words, one effect of this mission was added numbers of followers, and apparently, quite an expansion beyond Jesus’s provincial reputation. The radius of people now knowing about Jesus had grown, but by how much, we cannot know for certain. Eusebius centuries later than the four gospels maintained that he had read a correspondence between Abgar II, the ruler of Edessa, and Jesus (though the provenance of whatever Eusebius read is beyond sketchy, to say the least). For Edessa located well beyond northern Galilee to hear of Jesus by this time would have meant a considerably large preaching circuit for the Twelve. What the gospels do indicate is that people from neighboring regions of Decapolis, Gadara, and the coastal Mediterranean responded to news of Jesus’s miracles. At minimum, it appears his fame had spread to a circle about 80 miles in diameter, or around 5,000 square miles. In a news environment reliant on word of mouth, that would have been impressive, especially when we consider the timeframe since Jesus had begun preaching in public—a maximum about a year, but more likely a difference of only a few months.

Feeding the Multitude

We run into a conundrum from the gospel accounts: did Jesus miraculously feed a single multitude with a few loaves of bread and fishes? Or did he feed a multitude of 5,000 men with five loaves and two fishes, and then on another occasion feed a multitude of 4,000 men with seven loaves and a few little fishes? In both pericopes, the number only counts men in attendance; women and children were noted as being present but not counted. So we can’t say for certain how many were in the multitude.

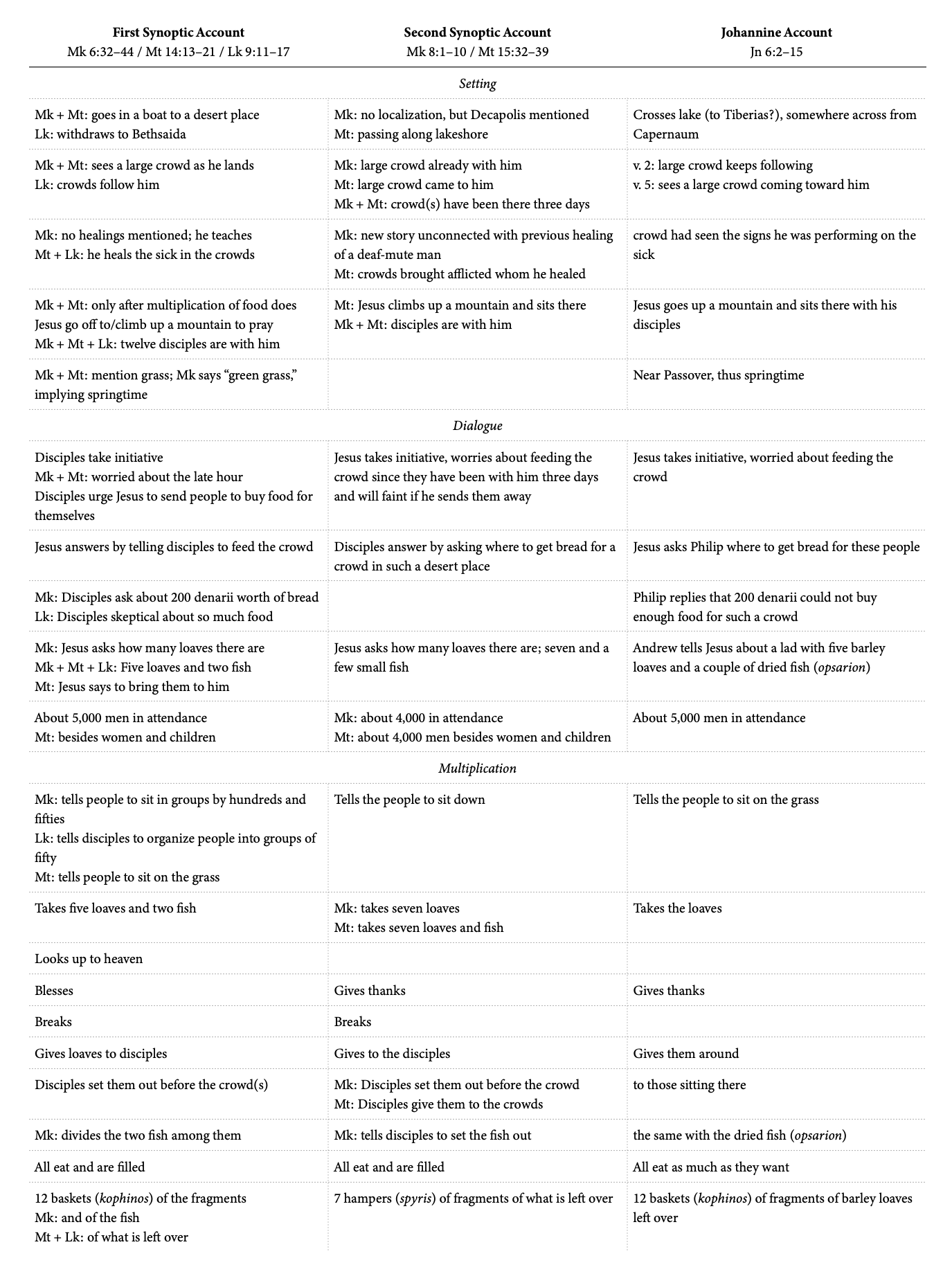

Let’s evaluate the two pericopes and see what emerges. The feeding of the five thousand appears in all four gospels (Mark 6:32–44; Matt. 14:13–21; Luke 9:11–17; John 6:2–15). The feeding of the four thousand appears in Mark 8:1–10 and Matt. 15:32–39. The conspicuous difference between pericope no. 122 (feeding of the five thousand) and pericope no. 129 (feeding of the four thousand) is the number: the one is marked by there being five thousand men in the multitude, and the other is marked by there being four thousand men.

We also have an aspect of the gospel of John that complicates pericope no. 122: the ample evidence that John was composed independently of the other three gospels and the ample evidence that the other three gospels were influenced by similar earlier sources (and in some cases, shared sources). A careful analysis will parse the first synoptic account of the feeding of the five thousand, the second synoptic account of the feeding of the four thousand, and the Johannine account of the feeding of the five thousand. John Meier and Raymond Brown plotted out the comparisons:

Notice from this chart three particular features of these pericopes: they all share in providing a setting, supplying some dialogue, and describing a multiplication miracle. Of all the miracles in the four gospels, this is the only one of “multiplication.” (The Cana miracle was a transformation of turning already existing water into wine.) Only minor variations appear between all versions, especially when compared to all the pericopes of the four gospels. So, it would seem these pericopes are describing the same event. But if there was only one feeding of the multitude event, why do Mark and Matthew repeat the story as though they were separate episodes? Let’s explore the possibility that Mark provided alternate versions of the same story. This possibility becomes more likely for the following reasons (described in Meier, A Marginal Jew, 2:956–957):

- The two versions in Mark in both content and structure are strikingly similar and in some details, virtually identical (especially in the Greek manuscript texts).

- The narrative between chapters 6 and 8 in Mark establishes continuity between both multitudes; in other words, these crowds heavily overlap in location and in following Jesus. And yet, the multitude in the second version seems totally unaware of Jesus performing a miracle of multiplying loaves and fish, what seems an exact repeat from before.

- John’s version contains elements of both versions in Mark, suggesting one early and fluid oral tradition got bifurcated in the copying of Markan manuscripts.

Something else worthy of note is how Mark’s second version applies virtually the same description of multiplying the bread as it does in describing Jesus and bread at the Last Supper, for example:

(Mark 8:6) and he took the seven loaves, and gave thanks, and brake, and gave to his disciples to set before them // kai labōn tous hepta artous eucharistēsas eklasen kai edidou tois mathētais autou

(Mark 14:22) and as they did eat, Jesus took bread, and blessed, and brake it, and gave to them // kai esthiontōn autōn labōn arton eulogēsas eklasen kai edōken autois

I provided the Greek so you can see how the words are almost identical (when one reduces grammatical suffixes to the root): lambanō (took), artos (bread), eucharisteō (gave thanks), klaō (break), didōmi (give) are the key words in both passages, and they’re the same in both (just properly declined and conjugated in Greek).

A prevailing hypothesis by biblical scholars is that the formulaic telling of the all-important eucharist—the breaking of bread at the Last Supper—that is well-attested across the earliest Christian culture region before any of the four gospels was written, got conflated with the miracle of feeding the multitude, and that this made an occasion for the episode to be duplicated. Basically, one version without the eucharistic formula, the other with it.

Regardless, the elements all converge such that the probabilities lean more toward one miraculous episode in history that, like the bread and fishes in the story, multiplied on the retelling, We could think of this episode as the “feeding of the multitude” as opposed to the “feeding of the five thousand” or the “feeding of the four thousand.” But that depends on how we wish to accept the accounts and how we wish to imagine them.

Barley and Fish

The detail about the bread and fish matters, I think, far more than the number of those in the multitude or the number of miraculous occasions. We know from historical sources how this particular region of Galilee supplied a grain surplus exported throughout the Roman empire. Sources also indicate how different grain varieties were used, as well as the fishing methods of that particular lake culture. Wheat grain was a staple for humans, the standard variety for making bread. Barley, however, was the cheap stuff, the variety used as animal feed. Also, the quality of the fish in this story was undoubtedly poor: a “few small” fish, or in John’s account, a “few small dried fish.” Fishermen sorted their catches, even if they intended their haul for their own families and not for business. This had to do with taxation. They tossed back small fish they couldn’t use and didn’t want counted.

A boy, only a boy in the crowd, had anything to eat, and all he had were a couple of small dried fish (that he probably had caught himself) and a loaf of barley bread. Animal feed. This wasn’t food, at least, not proper food, at all. Notice how the disciples relay this fact to Jesus with some tone of resignation: all we got is a barley loaf and two small fish; we have nothing to feed these people.

Just imagine the scene: they tell Jesus this, and he replies, Bring it to me. Bring me the animal feed and the poor boy’s meager, dried cat-food fish. And looking up to heaven, he gave thanks, and brake it. And it multiplied.

Do you hunger? Bring whatever you have, it doesn’t matter how meager, how poor, how seemingly useless it is, to Jesus. Watch him receive it, and give thanks for it, and multiply it for your wellbeing. There will be baskets’ worth left over.