An Anglophone’s New Testament Study Guide

(Long-ish) Introduction

The December 15, 2021, update to the Church’s General Handbook included new policy regarding use of the Bible: “When possible, members should use a preferred or Church-published edition of the Bible in Church classes and meetings. This helps maintain clarity in the discussion and consistent understanding of doctrine. Other editions of the Bible may be useful for personal or academic study.”1 This same update listed the King James Version of the Bible as the preferred edition for English-speaking wards and stakes.

I remember seeing some reaction online to this update, mostly from colleagues who expressed satisfaction seeing the official policy manual of the Church reflect what some within CES, Seminaries and Institutes, and other institutional settings had considered anathema—reading from biblical texts other than the King James Version. Only a very few, it seemed, noticed how this update represented a historical policy shift away from earlier decades when senior leaders in the Twelve and First Presidency debated among themselves whether to adopt the King James Version as the standard Bible for the Church.

Philip Barlow wrote the groundbreaking history of Mormons’ use of the Bible in his Mormons and the Bible in 1991.2 It documents the place and use of the Bible in the Church and places this biblical culture within the context of North American Christianity. In a separate article, Barlow addressed specifically the King James Version and why it was adopted as a standard edition in the Church.3

I wholeheartedly (and wholeintellectually) agree with Barlow’s observation: “The excellence of the King James Version of the Bible does not need fresh documentation. No competent modern reader would question its literary excellence or its historical stature. Yet compared to several newer translations, the KJV suffocates scriptural understanding.”4 Virtually every time I undertake a study of the original Greek texts of the New Testament (and the same holds true for the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, despite my relatively diminished experience in that subject area), I find the KJV, as Barlow put it, suffocating of scriptural understanding. It’s just not … the Bible; it’s King James’s fantasy of the Bible.

The history of how the KJV edged out other English versions to become the standard Bible in the Church is intricate and thick. Let me summarize: As public education became widespread in the late 1800s, Protestants and Catholics contended over which single version of the Bible the government should adopt for schools, which introduced new concerns among churchgoers across denominations about their own use of English translations. Meanwhile, so-called higher criticism of the Bible in the secular academy triggered theological backlash among conservative denominations and congregations, who took study of manuscripts and early biblical texts as pernicious attempts to alter doctrine. Within the Church, members generally misunderstood the language of Joseph Smith’s recorded revelations, assuming the King-James-sounding style was a divine endorsement of the KJV. When the RLDS Church published Joseph Smith’s Bible revision as the “Inspired Version” of the Bible, LDS Church leaders (strangely) took a stance against the Inspired Version and reinforced the doctrinal primacy of the KJV, mainly to discourage being seen as in agreement with a “rival” church. Within these contexts, J. Reuben Clark Jr., counselor in the First Presidency, sparked a showdown over the adoption of the KJV, contending against higher criticism, institutions of higher learning, and even members of the Twelve to defend the KJV as the definitive, pure text of the Bible in English. Barlow notes how Clark invented claims about Joseph Smith, for instance, that Smith used the KJV as the Bible of the Mormon tradition; “Joseph Smith would have been the last person to make allegiance to an inaccurate Bible an official practice when he knew of an alternative,” Barlow writes. “His use of the KJV was incidental to the time and location of his birth and, even then, he refused to be confined by it. The Book of Mormon itself scoffed at tradition-bound souls who refused progress in hearing the word of God.”5 What amounted to a campaign by Clark to defend against “apostasy” resulted with the release of the 1981 edition of the Standard Works in a hardline stance that the KJV was the Bible of the Restoration. English-speaking leaders and members have held a firm grip to this version ever since.

The update to the Handbook that acknowledges the utility of other Bible editions for study seems quite monumental to me, when compared with the intensity of feelings leaders after Clark showed toward the KJV. Yes, it’s probably only a drip in the glacier, but the glacier has receded compared to Clark’s overstated fears that abandoning the KJV amounted to abandoning faith in God.

Are other editions of the Bible useful for study? Most definitely. In fact, information available today eclipses what was available when the King James text was assembled, and I dare say even eclipses what was available when Clark mounted his campaign against non-KJV translations. For the New Testament, where can we turn to access the Bible itself (and not the whims of Anglican and Puritan clerks tendering an English version to appease a self-serving monarch)?

Resources

When the goal is for accuracy and linguistic precision, avoid theologically-driven translations like the New International Version (the best-selling translation in the United States), New Living Translation, English Standard Version, Christian Standard Bible, New International Reader’s Version, and the New American Standard Bible. Avoid also simplified Bibles that reduce the biblical text to elementary reading levels, like the Bible in Basic English, New Life Version, Simple English Bible, or The Message.

If the Bible is what you want, then let’s not apologize for the Bible being the Bible, which often means a challenging, dense, variegated, multivocal text. It sustains a whole academic discipline for a reason. Let’s not pretend on a presupposition that the Bible must be God’s word (a tautological premise) and that God’s word must be easy to comprehend (also a tautological premise); the texts that were later compiled into this literary thing we call the Holy Bible were what they were, are what they are, regardless of our desire for something more accessible.

Original Manuscripts

Nothing can replace going to the original sources and taking a stab at understanding them, even if one doesn’t have formal training in their languages and provenance. For one thing, it humanizes the New Testament and counters what some Christians have assumed (and sometimes stake their entire system of belief on) is a pristine text divinely transmitted from heaven without error, contradiction, or variation.

Institut für Neutestamentliche Textforschung, University of Münster. https://ntvmr.uni-muenster.de/catalog.

The most complete online resource for accessing all New Testament manuscripts. Hard to navigate unless you learn the indexing scheme for papyri, uncial, and other manuscript sources. Worth using anyway when tracking down a citation.

Novum Testamentum Graece (Nestle-Aland). 28th revised ed. Edited by Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland, Johannes Karavidopoulos, Carlo M. Martini, and Bruce M. Metzger. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2012. https://academic-bible.com.

The most complete critical edition of the New Testament. Also difficult to navigate without some familiarity with the Greek alphabet. Contains a textual apparatus for denoting all variants between manuscript sources of the New Testament texts as well as helpful indices of the numbering systems for identifying the sources. You can pull up any manuscript cited in this edition in the Münster catalog to reach the original sources directly and more efficiently.

Comfort, Philip Wesley and David P. Barrett. The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts. 3rd ed. 2 vols. Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic, 2019.

Presents the earliest identified manuscript text for each book of the New Testament and is among the most accessible resources for manuscript study for English speakers.

Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts. https://csntm.org.

Affiliated with the Center for the Research of Early Christian Documents, the CSNTM group is a non-profit research institution that works to digitize all New Testament manuscripts. Their digital collection is easier to navigate than the Münster catalog, but not as extensive.

Wikipedia. Lists of New Testament Miniscules, Uncials, and Lectionaries. In Category: Greek New Testament Manuscripts. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Greek_New_Testament_manuscripts.

I don’t often recommend Wikipedia, however, its list articles categorized under the Greek New Testament Manucripts page offer excellent tables of information that help with locating New Testament manuscripts.

Synopses

I’ve written before about how synopses (as opposed to harmonies) of the Four Gospels afford us better access to the original sources behind the gospels, since a synopsis arranges the contents of the gospels by their pericope structure. I find them indispensable for my study of the New Testament.

Aland, Kurt, ed. Synopsis of the Four Gospels: Greek-English Edition of the Synopsis Quattuor Evangeliorum. 10th ed. Stuttgart: German Bible Society, 1993.

Presents the original Greek text of each of the Four Gospels in column layout arranged by pericope; on the opposite page, presents the English translation from the Revised Standard Version. Also contains a text-variant apparatus, for studies of how manuscripts and early codices depart from each other.

Aland, Kurt, ed. Synopsis of the Four Gospels: English Edition. New York: American Bible Society, 1982.

Contains just the English half of the Greek-English Edition cited above. (Consequently, it tends to be half the price as well.)

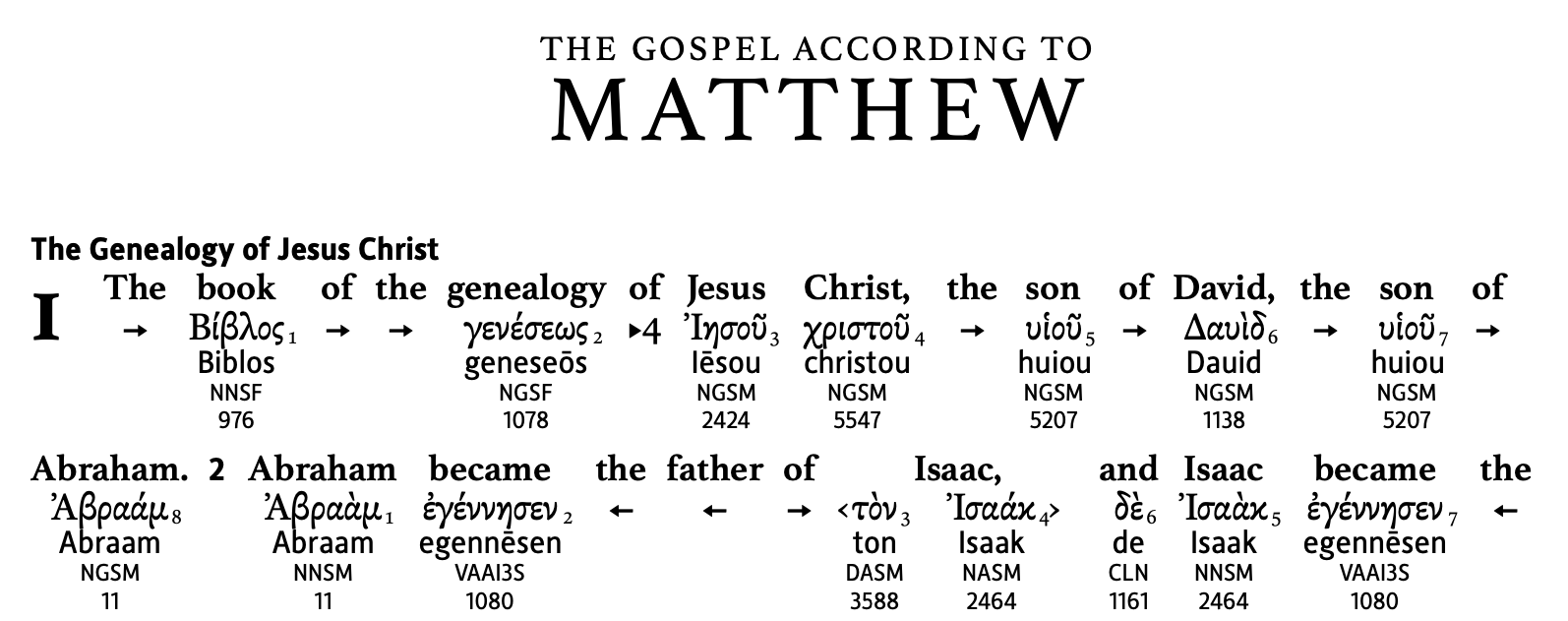

Interlinear and Word-study Resources

Interlinear texts present the original text in Greek with English translations aligned with the words/phrases for easier access to words, forms, grammars, and the like. Readers don’t need knowledge of Greek to start working with Greek texts, thanks to the formatting arrangement that makes the translations more explicitly linked.

Society for Biblical Literature. Lexham English Bible English-Greek Reverse Interlinear New Testament. https://sblgnt.com/download.

The PDF downloads contain the reverse interlinear formatting, as well as matching reference numbers to Strong’s Concordance. This means for each Greek word, you can look up the term by its Strong’s Greek number in websites like BibleHub or Blue Letter Bible.

Aubrey, Michael, John Schwandt, and Jake Parslow, eds. The English-Greek Reverse Interlinear New Testament New Revised Standard Version. Bellingham, Wash.: Lexham Press. Logos Bible Software. https://logos.com/product/154152/new-revised-standard-version-with-reverse-interlinear.

Similar to the SBL reverse interlinear edition using the Lexham English translation, this reverse interlinear digital edition uses the New Revised Standard translation against the Greek.

Diggle, J., et al. The Cambridge Greek Lexicon. 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

A multi-decades’ project to build a Greek lexicon from original research and the best studies to date of both Koine and later forms of the Greek language. It’s the best lexicon available and resembles the Oxford English Dictionary in its audacious scope. You’ll need a moderate to advanced reading ability of the Greek alphabet to navigate.

Lust, Johan, Erik Eynikel, and Katrin Hauspie, comps. A Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint. Rev. ed. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2003.

While this offers a lexicon for all terms that appear in the Greek Septuagint, an Old Testament text, the definitions often apply to New Testament Greek. Also requires reading knowledge of the Greek alphabet to look up terms.

Blue Letter Bible Institute. Blue Letter Bible. https://blueletterbible.org.

While its sponsoring organization is openly hostile to Latter-day Saint faith, its resources for word studies are quite useful. For each verse of the New Testament, you can open its “Tools” and access Strong’s numbers, transliterations of the Greek, and compare lexicon definitions and usages in ancient texts.

Logos. Bible Study App. https://logos.com.

Logos’s Bible software is second to none in the industry of study tools. Selecting any word in any translation of the Bible exposes additional word study tools that track original Greek lemmata frequencies, alternative meanings, parts of speech, concordance and lexicon entries, matching commentaries, and more.

Contextual Studies

Historical context can often be the most difficult to establish, especially since Christian denominations have for centuries disputed each other’s version of historical events and bases for historical interpretation. The academic space can be difficult to navigate, even for trained historians like myself. I recommend the following resources as useful starting points for building awareness of the historical problems surrounding New Testament research. A comprehensive reading list would be gargantuan.

The New Cambridge History of the Bible. 4 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013–2015.

These edited volumes bring readers up to date on the textual and historical scholarship surrounding the New Testament (and Hebrew Bible as well).

Ehrman, Bart D. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Bart Ehrman has earned a reputation among evangelical Christians in the United States as something of a heretic because of his disaffiliation from the evangelicalism of his youth and for his willingness to debate ministers about the New Testament. As a scholar, he has established himself as a careful reader of earliest texts and offers useful context for general readers. This peer-reviewed volume published by Oxford is excellent as an introduction to the histories surrounding the New Testament.

Pelikan, Jaroslav J. Jesus through the Centuries: His Place in the History of Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Jaroslav Pelikan is an eminent scholar of early Christianity who presents here a useful history of the figure of Jesus in Western culture. I find it a helpful survey for making sense of the many constructions and projections of Jesus that Christians have created for themselves.

Meier, John P. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus. 5 vols. New York: Doubleday, 1991–2016.

John Meier’s magnum opus, this 5-volume series examines in the most neutral style I’ve yet seen questions surrounding the historical Jesus, the texts and histories we can use to establish details about Jesus and his world, and the many debates that have ensued over the centuries and in modern scholarship. Meier was at work on a sixth volume when he died in October 2022; it’s unclear whether this will be published posthumously.

I personally prefer Meier’s approach to New Testament history and historical Jesus scholarship. He offered his studies as an outgrowth of this thought-experiment: imagine an “un-papal conclave” in which a Catholic, Protestant, Jew, Muslim, and agnostic scholar are locked in the basement of Harvard Divinity School until they arrive at a conclusion where they can each agree about Jesus of Nazareth purely on historical grounds and reasoning based on texts and records available.

MacCulloch, Diamaid. Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. New York: Viking Penguin, 2009.

One of the most detailed yet most accessible histories of Christianity ever written for non-specialists. Between this and its footnotes, readers are in solid shape accessing current expert knowledge about the settings of the New Testament.

Mitchell, Margaret M. and Frances M. Young, eds. The Cambridge History of Christianity: Origins to Constantine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

The whole Cambridge History of Christianity (9 volumes) is not for the faint of heart—the series offers top scholarship on Christian history. This first volume covers the periods overlapping the New Testament.

Translations into English

The number of English Bibles is immense. Each comes with its application of translation theory, its own theological or atheological approach, its own methodology, and its own range of vocabulary and reading level. An analogy from historical archaeology helps me think through selecting a translation to read:

A friend of mine works in the Historic Sites Division of the Church History Department, and once gave me a tour of the Beehive House on Temple Square. We discussed decisions their division had made in restoring the building and its decor. She asked me this question: But what version of the building should be our baseline for restoration? In other words, should they have restored the Beehive House to its original construction and decor? Or to a period in which Brigham Young introduced heavy innovations? Or when it served as a dormitory and the most people who ever passed through it experienced it?

When choosing an English translation, the translators’ theory and method resemble the archaeologists’ quandary about restoration: What formalities of language, what grammars, what vocabularies approximate the original? And which versions of the original manuscripts should govern the translation? You can ask yourself what you’re after as a reader—Do you want to “hear” the text as its authors did? Do you want to access “doctrine,” “theology,” or “philosophy”? Do you want poetry? Do you want prose? Do you want straightforward renditions that align with your common speech?

Lexham English Bible. Edited by W. Hall Harris III, Elliot Ritzema, Rick Brannan, Douglas Mangum, John Dunham, Jeffrey A. Reimer, and Micah Wierenga. Bellingham, Wash.: Lexham Press, 2010.

An attempt at a literal translation of the SBL Greek New Testament based on interlinear comparisons between Greek and English. Good for starting a word study but loses idiomatic touches and other nuances of Koine Greek expression.

Coogan, Michael D., ed. The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

The New Revised Standard Version of the Bible continues to drive most English quotations of New Testament texts in Anglophone scholarship. This annotated version is a top-shelf edition any serious student of the New Testament would benefit from consulting. Often a first recommendation by my biblical studies colleagues.

Hart, David Bentley. The New Testament: A Translation. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

My preferred translation. David Bentley Hart, an eminent classicist, turns his attention to the New Testament and captures so much of the odd constructions, common speech patterns, and other characteristics of the Greek manuscripts. Hart observes, “Most of the authors of the New Testament did not write particularly well, even by the forgiving standards of the koinē—that is, ‘common’—Greek in which they worked.… Over the centuries, the authors of the New Testament have profited greatly from translation; the King James Bible, among the greatest glories of our tongue, transformed their ‘common Greek’ into a very uncommon, though sublimely uncluttered, English.… Most translations, in evening out the oddities of the text, tend to flatten the various voices of the writers into a single clean, commodious style (usually the translator’s own). And yet in the Greek their voices differ radically; and I like to think that my version is somewhat more successful than most at capturing those differences.”

Open English Bible. https://openenglishbible.org.

A public domain, open-source, democratic translation of the Bible. As an experiment in crowd-sourced translation and verification, the OEB usually offers a highly literal translation into the most modern patterns of Internet English. I’m often surprised at the creativity of this translation and its formal accuracy, and usually bounce other translations off this one to get a sense of limitations of expression for a given passage.

Examples

For comparison, here are the Beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount/Plain in the Lexham, NRSV, Hart, and OEB translations:

Lexham English Bible

Blessed are the poor in spirit, because theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are the ones who mourn, because they will be comforted. Blessed are the meek, because they will inherit the earth. Blessed are the ones who hunger and thirst for righteousness, because they will be satisfied. Blessed are the merciful, because they will be shown mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart, because they will see God. Blessed are the peacemakers, because they will be called sons of God. Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, because theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are you when they insult you and persecute you and say all kinds of evil things against you, lying on account of me. Rejoice and be glad, because your reward is great in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets before you.

New Revised Standard Version

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled. Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God. Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. Blessed are those who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are you when people revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

Hart Translation

How blissful the destitute, abject in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of the heavens; How blissful those who mourn, for they shall be aided; How blissful the gentle, for they shall inherit the earth; How blissful those who hunger and thirst for what is right, for they shall feast; How blissful the merciful, for they shall receive mercy; How blissful the pure in heart, for they shall see God; How blissful the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God; How blissful those who have been persecuted for the sake of what is right, for theirs is the Kingdom of the heavens; How blissful you when they reproach you, and persecute you and falsely accuse you of every evil for my sake: Rejoice and be glad, for your reward in the heavens is great; for thus they persecuted the prophets before you.

Open English Bible

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are the mourners, for they will be comforted. Blessed are the gentle, for they will inherit the earth. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be satisfied. Blessed are the merciful, for they will find mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God. Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. Blessed are those who have been persecuted in the cause of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are you when people insult you, and persecute you, and say all kinds of evil lies about you because of me. Be glad and rejoice, because your reward in heaven will be great; this is the way they persecuted the prophets who lived before you.

Endless Possibilities

The number of potential resources expands cosmically—few fields in the humanities are as prolific and verbose as biblical studies and history of Christianity. I recommend some criteria when evaluating a resource for your New Testament studies:

What is the theological or philosophical orientation of the author(s)? When you’re clear on your own commitments to the facts of history and the limits of our conclusions on the New Testament text, you can evaluate against your own purposes which resources align best. For instance, because I’m committed to a neutral, source-based, limited, careful study, I don’t find many LDS-sponsored resources all that helpful; they’re theological commitment—before engaging any source—toward a particular view of Jesus interrupts the source-based empirical approach I’m interested in. But that’s my own approach at play; everyone’s will be specific to them and their study needs.

What is the exigency that moves the author(s) to write? It’s quite different for one author, like Meier, to want to understand the historical Jesus on whatever terms the historical sources present, and for another, like James E. Talmage, to want to articulate a deep portrait of the glorified Jesus to counter the higher criticism of the 1910s. Each author will have some kind of exigency behind their work, some kind of energy moving them to write. Getting clear on their exigencies can really help with evaluating whether and how their work will align with your study objectives. Someone may have written a fine piece of work, but because their exigencies depart from yours, it becomes a coin-flip sometimes whether their work will prove worthwhile for you.

What is the author(s) posture toward the intended audience? A lot of New Testament commentaries imply hostile interlocutors just trying to gainsay whatever one might interpret from the scriptures. This goes many directions: secular interlocutors skeptical of theological approaches, devotional readers skeptical of scientific or empirical methodologies, or hardline believers unwilling to consider anything that doesn’t portray Jesus or the Apostles according to their own worship-stance. Finding how the posture of the author(s) toward the intended audience helps to evaluate whether you align or misalign with their methods and approaches. I’ve spared myself some heartburn by quickly determining one author or another doesn’t want to engage with my interests or concerns, and then setting aside the book for something more helpful.

General Handbook, “Editions of the Holy Bible,” 38.8.40.1, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/general-handbook/38-church-policies-and-guidelines?lang=eng#title_number139. ↩

Philip L. Barlow, Mormons and the Bible: The Place of the Latter-day Saints in American Religion, updated ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013). ↩

Philip L. Barlow, “Why the King James Version? From the Common to the Official Bible of Mormonism,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 22, no. 2 (Summer 1989): 19–42, https://www.dialoguejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/sbi/articles/Dialogue_V22N02_21.pdf. ↩

Barlow, “Why the King James Version,” 19. ↩

Barlow, “Why the King James Version,” 33. ↩