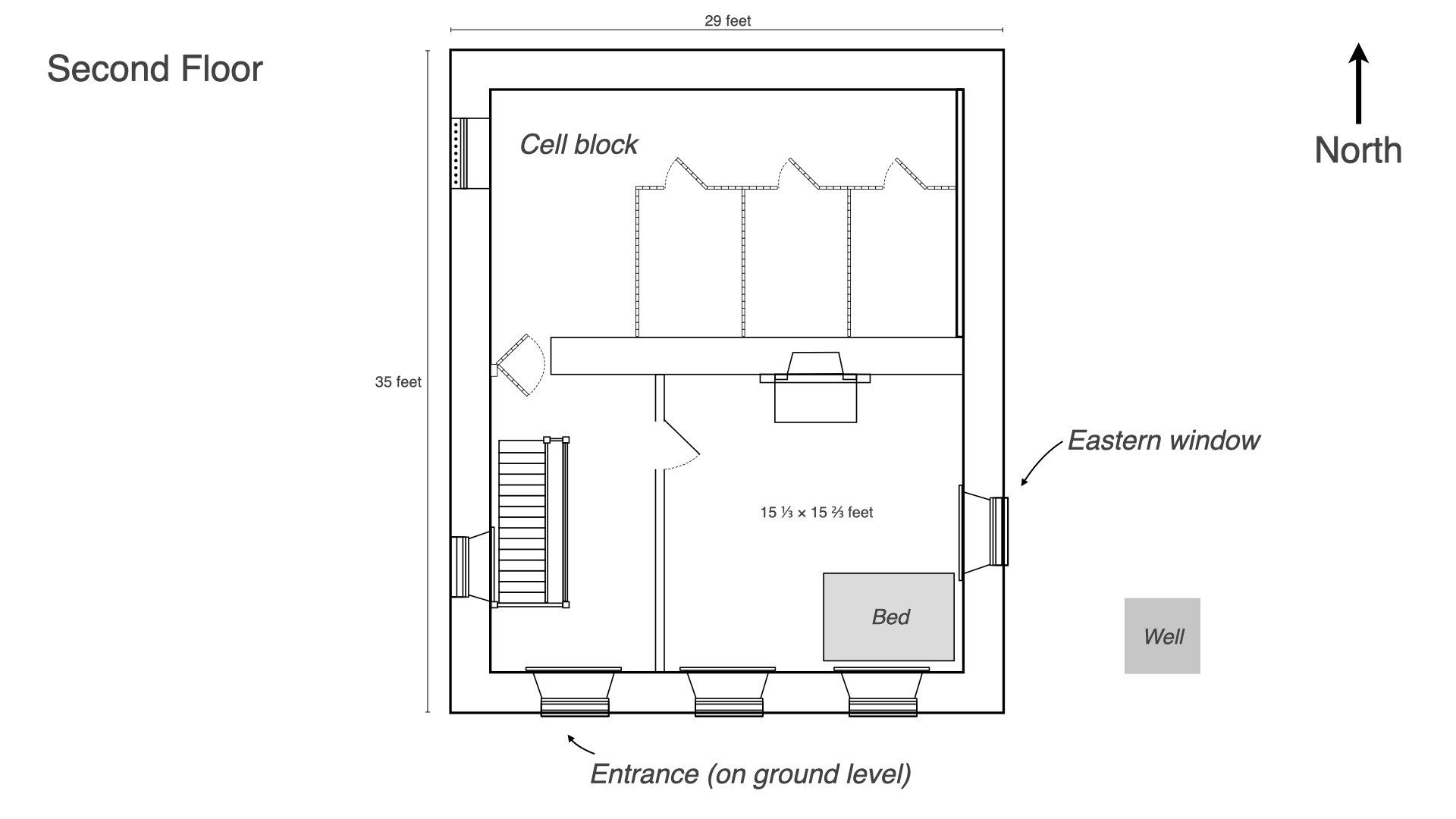

The second floor of Carthage Jail supported a security cell fitted with iron bars that spanned the north and west sections of the building. On the southeastern corner was the jailer’s bedroom: fifteen-and-a-half feet square, with two interior walls on the north and west edges, and two exterior walls on the south and east edges. The room opened through a single door on the western wall at the northern corner, which, facing out, was hinged on its right side. A fireplace stood midway along the northern interior wall, and a regular-sized bed was nestled against the southeastern corner diagonally opposite the door. A single window on the eastern wall overlooked a water well outside. Two windows on the southern wall looked out toward the center of town and stood above the entrance to the building. The windows measured between eleven and twelve feet above the ground outside.

The jailer, George Stigall, allowed four prisoners—Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, John Taylor, and Willard Richards—to remain in his bedroom instead of the jail cell while the men awaited a hearing at the county courthouse a couple of blocks away. The day was warm, and only Richards kept his jacket on. Joseph, Hyrum, and Taylor hung theirs on a rack. They opened the eastern window to ventilate the otherwise stuffy quarters. The mood was dull and languid, a “remarkable depression of spirits.” Taylor thought of a new song in Nauvoo that was “pathetic and plaintive” enough to match his feelings. To the tune “Duane Street,” he sang “The Stranger and His Friend,” later titled in Latter-day Saint hymnals, “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief.” He remembered later how it “surcharged” the “indefinite, ominous forebodings” they all sensed.

A poor, wayfaring man of grief

Hath often cross’d me on my way,

Who sued so humbly for relief,

That I could never answer, Nay.

I had not power to ask his name,

Whither he went, or whence he came,

Yet there was something in his eye,

That won my love, I knew not why.

Once, when my scanty meal was spread,

He enter’d—not a word he spake—

Just perishing for want of bread,

I gave him all; he bless’d it, brake

And ate, but gave me part again—

Mine was an angel’s portion then;

And while I fed with eager haste,

The crust was manna to my taste.

I spied him where a fountain burst,

Clear from the rock; his strength was gone;

The heedless water mock’d his thirst;

He heard it, saw it hurrying on.

I ran and raised the sufferer up;

Thrice from the stream he drain’d my cup,

Dipp’d, and return’d it runner o’er;

I drank, and never thirsted more.

’Twas night; the floods were out; it blew

A wintry hurricane aloof;

I heard his voice abroad, and flew

To bid him welcome to my roof.

I warm’d, I clothed, I cheer’d my guest;

Laid him on mine own couch to rest;

Then made the earth my bed, and seem’d

In Eden’s garden while I dream’d.

Stripp’d, wounded, beaten nigh to death,

I found him by the highway side;

I roused his pulse, brought back his breath,

Revived his spirit, and supplied

Wine, oil, refreshment; he was heal’d.

I had, myself, a wound conceal’d;

But, from that hour, forgot the smart,

And peace bound up my broken heart.

In prison I saw him next, condemn’d

To meet a traitor’s doom at morn;

The tide of lying tongues I stemm’d,

And honour’d him ’mid shame and scorn.

My friendship’s utmost zeal to try,

He ask’d, if I for him would die:

The flesh was weak, my blood ran chill,

But the free spirit cried, “I will!”

Then, in a moment, to my view

The stranger started from disguise;

The tokens in his hands I knew—

My Saviour stood before my eyes!

He spake, and my poor name he named:

“Of me thou hast not been ashamed;

These deeds shall thy memorial be;

Fear not; thou didst it unto me.”

After some time, Hyrum asked Taylor to sing it again.

“Brother Hyrum,” Taylor replied, “I do not feel like singing.”

“Oh, nevermind! Commence singing and you will get the spirit of it,” Hyrum said.

Taylor sang it again.

Hyrum, who had brought copies of the Book of Mormon and other books with him, read to the group from The Works of Flavius Josephus, an ancient chronicler of the Jewish people in Roman Palestine. At four o’clock, the guards changed, leaving seven at the jail. The Carthage Greys, the town’s militia, camped at the town square a quarter-mile away per governor’s orders. The governor of Illinois, Thomas Ford, who had inspected conditions that morning, expected the dozens of soldiers to serve as additional protection for Joseph Smith while he left with a unit of state militia to broker an armistice in Nauvoo. The prisoners kept up conversation with each other and the guards, more or less waiting out the day.

Suddenly, Stigall popped in, anxious. He had encountered Stephen Markham near the town square. Markham, who had left earlier to bring tobacco for Richards’s upset stomach, met one of the Greys on his way back to the jail who demanded Markham leave Carthage in five minutes. When Markham refused, the soldier charged him with his bayonet, but Markham knocked the man down. Other Greys quickly surrounded Markham, threatened to kill him unless he left town, and prodded him with bayonets until he mounted his horse. Stigall had watched them escort Markham toward the edge of town and now suggested that the prisoners retreat to the holding cells for better safety. The jailer resumed his errands and left things to the latest shift of guards.

“If we go in the jail, will you go in with us?” Joseph asked Richards.

“Brother Joseph,” Richards said, “you did not ask me to cross the river with you. You did not ask me to come to Carthage. You did not ask me to come to jail with you. And do you think I would forsake you now? But I will tell you what I will do: if you are condemned to be hung for treason, I will be hung in your stead, and you shall go free.”

“You cannot,” Joseph said.

“I will,” Richards insisted.

One of the guard’s boys entered with some water. A guard sent the boy to fetch some wine. Joseph offered two dollars fifty, but the guard gave back all but one saying a dollar was enough. As Markham hadn’t delivered the pipe and tobacco, the boy left to bring those as well. He soon returned, and Richards uncorked the wine bottle and poured glasses for Joseph, Taylor, and himself. They drank and handed the bottle to a guard. While Taylor sat at the thick alcove of one of the southern windows overlooking the jail’s entrance, he began to notice a number of men with painted faces rounding the corner below toward the front door. From the top of the stairs, the guard heard someone call to him two or three times. He descended the stairs, and within a moment, Joseph and his companions heard some rustling at the entrance. Richards peered through the curtain in a south window and saw a hundred men or so now surrounding the front.

The guards made a cry of surrender and immediately three or four rifles discharged, possibly a signal to the Carthage Greys of their premeditated ambush, or blanks shot by the guards feigning a stalwart attempt to stay the mob. The vigilantes punched through the door to the staircase directly in front of them, and the attack was on.

Joseph sprang to his coat on the rack to pull a six-barreled revolver from its pocket that a friend had smuggled to him that morning. Hyrum did the same, securing his single-barrel pistol, another smuggled weapon. Taylor and Richards each snatched a walking stick. The four shut the bedroom door and braced it with their bodies, leaning from the hinge on the right-side corner. They found no lock on the door, and the upper latch on the frame was useless. The door itself was made of common panel board, not nearly thick enough to offer any security against gunshots.

The attackers stormed the stairway, firing muskets toward the two doors facing them on the second story, assuming the prisoners could be held in one of the two rooms. A ball punctured the bedroom door, leaving a hole. They tried to open the jailer’s bedroom door and detected the prisoners’ resistance. Someone fired at the door handle and keyhole to break it open. The round whizzed between the men on the other side.

This persuaded the defenders that their assailants were reckless, since the attackers should have assumed the prisoners were armed, and to fire so directly in front of the keyhole was to expose oneself foolishly to a firefight. The four opted to maneuver, figuring a different position would improve their defenses. They might scare away the men at the bottleneck of the stairway if they could get some shots off.

Joseph, Taylor, and Richards shifted leftwards from the hinge while Hyrum retreated a few steps back to face the doorway at a diagonal. They let the door inch open for Hyrum to take aim. He snapped his pistol but was immediately met by a shot to the face, knocking him flat, vertical, and extended, onto his back without him moving a foot. “I am a dead man!” he shouted.

Joseph rushed to Hyrum, leaning over him while Taylor and Richards braced against the door. “Oh, my poor, dear brother Hyrum!” Joseph cried. With a firm step and “determined expression of countenance,” he pivoted back to the door, let the door open two or three inches, then angled his revolver with his left hand around the opening and blasted away all six rounds of his tiny revolver. Only three shots flew, the others misfiring. Mobbers at the door still propelled their musket barrels and bayonets through the crack, firing at will. Taylor batted them down with his cane. While both sides exchanged fire, at least one attacker was hit, quelling the pressure for a brief moment. Richards stood ready like Taylor to bat away the poking rifles, but couldn’t get much purchase without exposing himself to the muzzles.

After Joseph had emptied his revolver, he quickly switched positions with Taylor, who was standing close behind. The attackers shoved at the door with a hard push and again worked their rifles through the door, now gaining a wider berth in the room. Another volley blasted through, Taylor still parrying at them with his cane, and briefly and successfully redirecting the rounds away from the men. “That’s right, Brother Taylor,” Joseph said, “parry them off as well as you can.”

The assailants crowded more densely at the door, pushed on by more heaving upward from below all the way back to the jail’s entrance. Taylor could hear the clamor of swearing, shouting, cursing, and gunfire—“pandemonium let loose,” he later called it. He could only parry the guns a little while longer before the muskets thickened and protruded further into the room.

Seeing no abatement and expecting a harder rush any moment, Taylor remembered seeing the Carthage Greys standing some 50 to 65 yards off the east end of the jail. The eastern window faced obliquely away from the entrance and the mob, offering, however foolhardy, a possible line of escape. He reckoned that the intense pressure at the door now invited certain death. The eastern window was already open.

Taylor leaped to the window, gained the alcove, and was nearly on a balance to lower himself outside when a musket ball struck him midway up the thigh, punctured his femur, and pinched or severed a prominent nerve that instantly paralyzed his whole right leg. He dropped hard onto the alcove, crying out, “I am shot.” His pocketwatch crushed against the windowsill, freezing its hands at 5:16 and 26 seconds p.m.

As Taylor nearly slipped out the window, another round hit his wrist, whipping his arm back and pushing him into the room. Now on the floor, Taylor began to crawl underneath the bed in the corner. All the while, Richards had purchased some relief with his cane, parrying the rifles while other attackers reloaded their muskets and prepared a volley. Fearing another round from Joseph’s gun, men at the very top of the stairs shifted to the long side of the hallway, firing left-handed, which slowed their volleys and cheapened their aim. In an instant, the door heaved further, and as Taylor reached for shelter under the bed, a barrage of gunfire pelted the room. Two more rounds hit Taylor, one squarely in the left hip ripping out a mass the size of his fist that splattered the wall, and another lodged below the left knee, never to be extracted. The sensation made Taylor believe he had lost his entire left leg, and the shocking image of being an invalid should he survive flashed across his mind.

In the slight interval between another rush at the door and musket reloads, Joseph now attempted Taylor’s escape. With Joseph off the door, it flung wide open, pinning Richards into the hinge corner and exposing Joseph to lines of fire from both sides of the eastern window. In that split second, Joseph cried, “O Lord my God!” Rifles fired—two rounds from the doorway struck him, and possibly another one or two from outside. Richards had leaped toward Joseph at the same time, narrowly missing the gunfire, his coat taking a hole, his ear catching a graze, and a strip of his facial hair getting mowed and singed. He saw Joseph fall out the window precisely with the blast, and continued rushing to the window only to watch him land on his left side, face first. “He’s leaped the window,” someone shouted. The shooting stopped. Attackers inside rushed downstairs toward Joseph on the ground outside.

Richards retreated from the window, thinking it futile to “leap out on a hundred bayonets.” He cautiously took another look at Joseph and could see no signs of life. The men outside were quickly converging around Joseph’s body. Richards flew back to the doorway expecting another attack and peered around the head of the stairs to learn if the high-security cell was open next door. “Stop, doctor, and take me along,” Taylor said from beneath the bed. Richards noticed the cell doors were unlocked, opened the iron cage, and ran back to recover Taylor. Dragging Taylor into the inner prison cell, he laid him on the hard floor and said, “Oh, Brother Taylor, is it possible that they have killed both Brother Hyrum and Joseph? It cannot surely be, and yet I saw them shoot him.” Standing over Taylor and elevating his hands two or three times, Richards cried, “O Lord my God, spare thy servants!” He turned to Taylor. “Brother Taylor, this is a terrible event.”

Richards pulled Taylor farther into the cell, apologizing for not doing better, then draping an old, filthy mattress on top of him. “That may hide you,” Richards said. “It is a hard case to lay you on the floor, but if your wounds are not fatal, I want you to live to tell the story. I expect they will kill me in a few moments.” Terrible pain racked Taylor while he tried to hide. Richards stood behind the inner prison door, waiting for a renewed assault, expecting more bullets.

Meanwhile, a resident from Augusta near Carthage named William Daniels stood among fellow militiamen outside and saw Joseph plummet from the window. He believed Joseph had survived the fall and swore he could see one of the commanders, Levi Williams, reach Joseph, pull Joseph’s body against the well, and order others to take aim and fire.

Some others ran back upstairs and spotted Hyrum’s dead body on the floor, then either standing over him or from the doorway, fired another three shots at him—one through the chest that exited the back, one through the left leg below the knee, and one through the right thigh. From under the straw mattress, Taylor could hear the men sneak back down the stairs out of the jail.

The mob outside began to scatter. In the confusion, witnesses couldn’t be sure whether anyone had followed Williams’s order, pulled a trigger, and delivered more gunshots to Joseph. In the post-mortem, coroners discovered four total wounds.

Richards stepped out to confirm that the attack had dissipated, saw Hyrum’s body unchanged since falling, and Joseph’s body slumped against the well. He returned to Taylor and told him the awful news. “I felt a dull, lonely, sickening sensation,” Taylor remembered. Soon, Richards pulled Taylor out of the cell and onto the floor at the top of the stairs while he left to find help. Taylor glanced back toward the jailer’s bedroom and saw Brother Hyrum still there. “He had not moved a limb,” Taylor noticed. “He lay placid and calm, a monument of greatness, even in death.”

George Stigall and other Carthage townspeople came around, bringing a physician and local coroner, Thomas Barnes. Barnes treated the musket ball in Taylor’s hand first, using a penknife and a pair of carpenter compasses to triage the wound. Sawing through flesh between the third and fourth fingers with the rude tools, he finally pried the half-ounce ball loose. Taylor thought the ordeal “surgical butchery” and an offense to medicine.

Barnes noticed the straw had adhered to the clothes along Taylor’s wounds, helping to coagulate the blood and slow the bleeding. Still cowering behind the edge of the cell area, covered in bloody straw, and visibly frightened, Taylor looked a “pitiable sight.” Barnes and Stigall tried to persuade Taylor to remove to Hamilton’s Hotel a block away where the prisoners had already lodged before their incarceration. Taylor refused, considering it totally unsafe. Barnes protested to assure Taylor he was protected. Townspeople expressed outrage at what had just happened and promised they were friends. “I don’t know you,” Taylor insisted. “Who am I among? I am surrounded by assassins and murderers. Witness your deeds! Don’t talk to me of kindness or comfort! Look at your murdered victims! Look at me! I want none of your counsel nor comfort. There may be some safety here. I can be assured of none anywhere else.” Cursing to themselves, swearing by God and the devil and “everything else they could think of,” they pledged to stand by Taylor to the death and protect him. Within the half-hour, Taylor remembered, “every one of them had fled from the town.”

Carthage being the county seat, other coroners were on hand to assess the carnage, and Barnes started the coroner’s jury with Richards. They assembled near Hyrum’s body, whose head Barnes noticed lay against the wall. As Richards recounted to Barnes the sequence of events, Taylor looked on, writhing and anxious. The men spoke of ways to convey the bodies back to Nauvoo. “What does all this mean?” Barnes asked Richards. “Who has done it?”

“Doctor, I do not know,” Richards said. “But I believe it was some Missourians that came over and have killed Brothers Joseph and Hyrum and wounded Brother Taylor.”

“Do you believe that?”

“I do.”

“Will you write that down and send it to Nauvoo?”

Richards said he would if Barnes could deliver the message. If Richards wrote that much, Barnes promised to send it. Richards agreed. When they furnished the letter a couple of hours later, Taylor’s hand still trembled enough for him to worry that relatives might notice the unsteady handwriting and suspect his condition was worse than it was. Richards would write, “Taylor wounded not fatally”; Taylor would have him change it to “not very bad,” even while his wounds remained exposed and his status uncertain.

Richards turned to Taylor and suggested they make for Hamilton’s tavern. Trusting only Richards, Taylor consented and exited the cell block at the top of the stairs—his bloodied, strawed costume provoking shock and awe not unlike the classic implement of lynchings at the time, tar and feathers. Moving Taylor proved excruciating. Other townspeople already had begun to flee at rumors of a Mormon counterattack. The Nauvoo Legion militia outnumbered the mob twenty times over. Finding enough people to carry Taylor took longer than moving Joseph’s body from the well to a table in the jail’s entryway. As they carried Taylor down the stairs, Barnes was already inspecting Joseph’s wounds that still dripped blood on the carpeted floor. Amid the disarray and while alarm cannons still fired nearby to signal that citizens stay indoors, Taylor and Richards crossed the quarter-mile distance to the town square and finally made it to the hotel. As a matter of course, Barnes issued a receipt of one dollar for medical services rendered (he had recently lost almost all his spare belongings to bad debt and was desperate for money) that Taylor considered an affront during an emergency and refused to pay.

Sometime but not long after, Samuel Smith appeared. Samuel lived in Plymouth fourteen miles away from Carthage in the opposite direction of Nauvoo. He had already left to visit his brothers at the jail that afternoon, not knowing of militia companies mobilizing throughout the day to make an assault. He had set off on horseback for a direct and easy ride to Carthage. Now at the hotel, he informed Taylor and Richards that on the way, he had intercepted a band of militiamen, who, upon learning Samuel was Joseph Smith’s brother, opened fire. Having a reputation as an excellent horserider, Samuel said it took his greatest skill to outmaneuver their gunshots. After “severe fatigue and much danger and excitement,” Samuel closed in on Carthage, suspecting a terrible siege beset his brothers. Learning the worst left him “very much distressed in feelings.”

Samuel and Richards consulted with each other about how to remove the bodies from hostile and uncertain Carthage. They supposed their enemies would disgrace the bodies, maybe even make a display of vigilante threats with them. Whatever they accomplished must be done with utmost secrecy.

Taylor lay at the hotel through the night without anyone dressing his wounds and help in Carthage rapidly evaporating. Word was sent to Taylor’s wife, Leonora, and his parents, who searched for a friendly physician to help. They found Samuel Bennett, who made it to Carthage at 2:00 a.m.

Sources

Principal Observers

“Awful Assassination!” Nauvoo Neighbor—Extra, broadside, June 30, 1844.

“Statement of Facts!” Times and Seasons 5, no. 12 (July 1, 1844): 561–564.

John Taylor, “Wilful Murder!” Nauvoo Neighbor 2, no. 10 (July 3, 1844): 3.

“The Murder,” Times and Seasons 5, no. 13 (July 15, 1844): 584–586.

Willard Richards, “Two Minutes in Jail,” Nauvoo Neighbor 2, no. 13 (July 24, 1844): 3.

Indictment, 26 October 1844, State of Illinois v. Williams, et al., Hancock County, Illinois.

Other Primary Sources

B. F. White and E. J. King, The Sacred Harp: A Collection of Psalm and Hymn Tunes, Odes, and Anthems, Selected from the Most Eminent Authors (Philadelphia: T. K. and P. G. Collins, 1844).

Copy of Death Mask of Joseph Smith (“Dibble Mask of Joseph Smith”), mold by George Cannon, 29 June 1844, LDS 90-12-6, Church History Museum, Salt Lake City.

Copy of Death Mask of Hyrum Smith (“Dibble Mask of Hyrum Smith”), mold by George Cannon, 29 June 1844, LDS 90-12-7, Church History Museum, Salt Lake City.

Secondary Sources

Joseph L. Lyon and David W. Lyon, “Physical Evidence at Carthage Jail and What It Reveals about the Assassination of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” BYU Studies 47, no. 4 (2008): 4–50.

Debra Jo Marsh, “Respectable Assassins: A Collective Biography and Socio-Economic Study of the Carthage Mob” (master’s thesis, University of Utah, 2009).

E. Gary Smith, “Blood, Bullets, Pistols, and Martyrs: A New Look at Solving a Carthage Jail Mystery,” Journal of Mormon History 45, no. 4 (October 2019): 1–37.