Matthew’s presentation of the Sermon on the Mount introduces Matthew’s key theme for the whole gospel: Jesus’s emphasis on the “kingdom of heaven.” The other gospels develop this theme using the term “kingdom of God,” and all together affirm a revolutionary concept in Jesus’s time that set him apart from contemporaries as a true original. For the Gospel of Matthew, this kingdom of heaven/kingdom of God lay at the center of Jesus’s whole message—when understood, it explains everything else Jesus taught.

Like the Beatitudes and Woes, we have a translation concern that can greatly affect how we interpret this concept. The word in the Greek is basileia, what gets translated into King James English as “kingdom.” Of course the King James committees who undertook the order to render a kingly Bible and dedicated their work to the majesty of a king would maintain and insist on basileia = kingdom. Their world was so thoroughly sustained and infused by monarchy, we can hardly expect them to think outside this box. But as we have already noticed in Sermon, Jesus challenged the status quo of his time and offered radical reinterprations of Torah, to say nothing of the Roman imperium, to his audiences. As we’ll see, those audiences struggled to wrap their minds around Jesus’s revolutionary new world. Jesus continually urged them to see the world differently, to see how God’s realm didn’t compete with Rome or any other empire or nation-state, but was always-already imminent. Disciples initially and then for centuries treated this teaching as a kind of mystery.

Immediate Literary Context

Let’s keep this word basileia in its immediate literary context—where it appears within a series of teachings. Jesus speaks of the basileia within teachings pronouncing woes on decorous speech. “Woe unto you, when all men shall speak well of you!” he said, which in its historical context and in the original Greek as we’ve already noted, referred to societal divisions between upper-class aristocrats and lower-class commoners and the deferential flattery enforced by those of higher status against those of lower status. When people must refer to “your majesty” and similar elevated tones rather than speak human to human, it was this dynamic of possible impertinence at the heart of this woe. Jesus eschewed such pretentions, even juxtaposing this behavior against the poor, the gentle, the bereaved, to draw the distinction loud and clear. So, given this precise moment in the sermon, right as Jesus then speaks of the basileia of the heavens: are we comfortable assigning the very same elevated, monarchical pretention and status embedded in the word king? Unless it’s the unmistakable rhetorical device of irony—which I doubt is the case here—king-dom, literally meaning “domain” of a “king,” seems inappropriate, even counter to the driving force of how Jesus introduces the sermon.

What’s more—the Greek prefix basile- referred more often in ancient texts to prerogative or occupying a decision-making position within or over something. Monarchs did use basileia to refer to their kingdoms, and so “kingdom of heaven” and “kingdom of God” are not altogether mistranslations. But, remembering the immediate context for the Sermon on the Mount/Plain, and remembering how Jesus displayed more rhetorical deconstructions of commonly used words, redefining those words with visuals that broke from the typical, I favor a generic use of the word basileia that doesn’t perpetuate the English word “king” or any other monarchical title. The word “dominion” fits the bill better than alternatives in my view, though I admit this suits my own subjective preferences; words like “domain” and “realm” can also apply to basileia.

I don’t insist on “dominion of God” or “dominion of heaven” (or the more literal rendering of the Greek, “dominion of the heavens”) when discussing the Gospels in mixed company. Most readers would get lost without this lengthy preface to my use of “dominion of God,” and so the utility of the more nuanced translation suffers in most public settings, I think. But I do hope to lend some observations about language and translation to refine our assumptions and imaginations about Jesus’s descriptions of a heavenly society and our own kingdoms, governments, and other social constructs.

As a dominion, such a heavenly society can coexist within any other society; we can belong to this dominion and participate within it no matter whether we’re Galilean peasants or modern Americans or living in Antarctica. When some disciples pressed Jesus to smash the Romans, he pushed back, insisting that God’s work called for a transformation, not a rebellion.

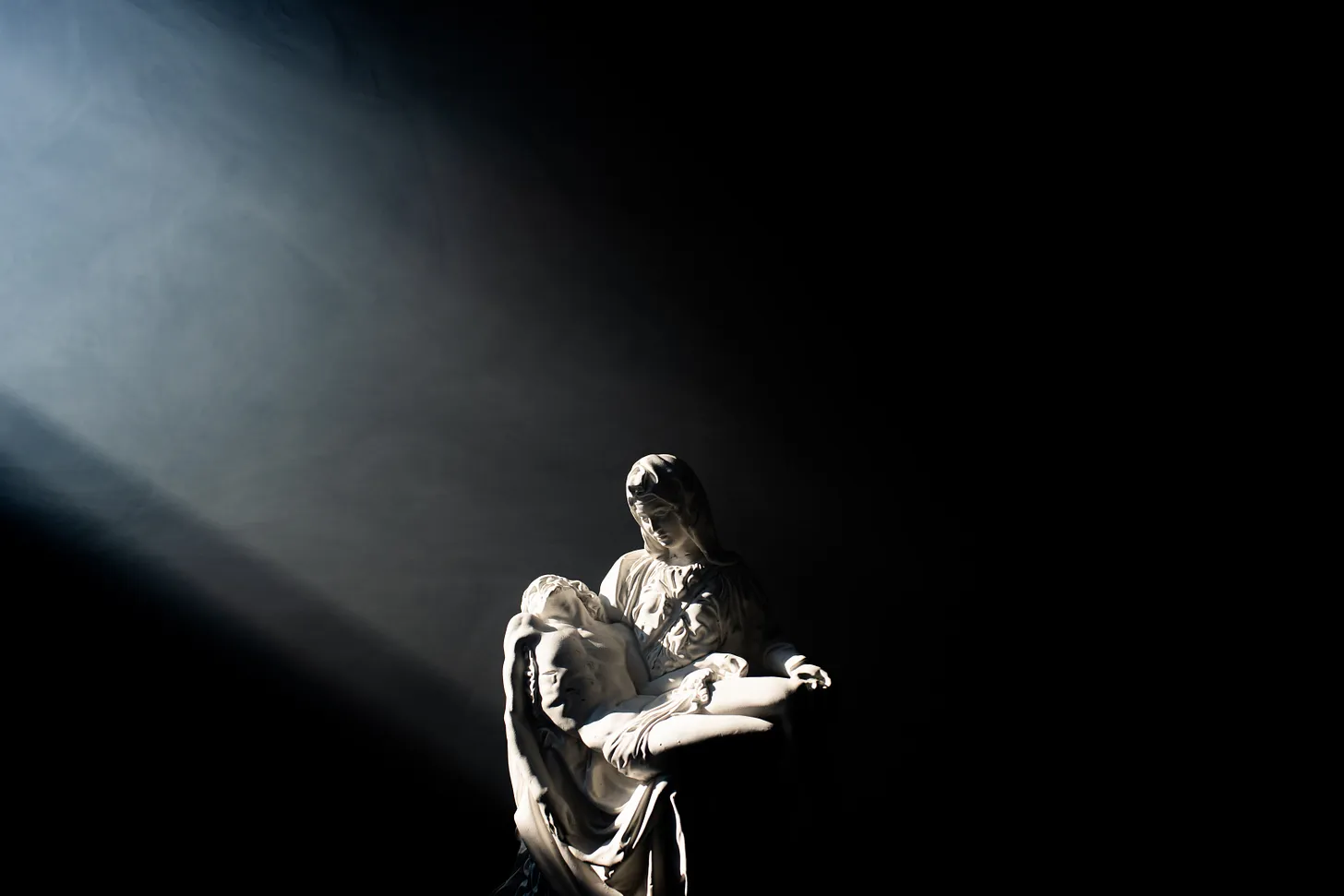

Holy Week and Easter

Today is “Spy Wednesday” in the traditional Holy Week of Western Christianity. I thought I might relay some thoughts about Holy Week in case it might be interesting to you as you celebrate.

What’s with the Shifting Date of Easter?

Ever wonder why Easter shifts every year, and why it’s not as simple as the calculation for Thanksgiving (the fourth Thursday of November)? Well, it’s a doozy and one of the most curious and strange developments in Christian history. There’s the long answer—and believe me, it can get very long and obtuse—and there’s the short answer. And the short answer is convoluted, no matter how we slice it. Here’s the simplest way I know of explaining how we arrive at a date for Easter.

It all comes down to Christians wanting to nail down the precise day Jesus rose from the tomb and basing that day relative both to Passover and to springtime. The Jewish Passover in Jesus’s time and today follows a lunar calendar (ours is a solar calendar). But the seasons turn with earth’s orbit around the sun. So we’re getting a confusing convergence of a lunar calendar and a solar calendar.

OK, so think of it this way: the gospels have Jesus resurrecting on the first day of the week, which means Sunday; they also have Jesus dying on the cross the day before the Passover festival, which was always observed in ancient Judaism during the Jewish month of Nisan (in the spring); and Passover began at the rising of the moon at twilight. The vernal equinox is an astronomical event that marks when the position of the sun in the sky starts to return toward being directly overhead—the earliest possible beginning of spring. So, the earliest Passover window after the start of spring would be the first full moon on or after the vernal equinox.

There we have it: Easter Sunday is the first Sunday with or after the first full moon after the vernal equinox.

But we have one big wrench that messes with this formula—the Catholic Popes contending against the Orthodox Patriarchs during the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods. In Catholicism, Pope Gregory revised the church’s calendar from its previous Roman standard (for reasons we’ll avoid at the moment); this “Gregorian calendar” is the one we’re presently using for our months, weeks, and days of the year. In Eastern Orthodoxy, the Patriarchs continued to use the Roman/Byzantine “Julian” calendar. So even if we apply this same formula, the Gregorian and Julian calendars will give us different dates for Easter because the Gregorian system makes March 21 too early for a springtime full moon.

The vernal equinox almost always occurs on March 20 of every year (this was true of 2023). The first full moon after March 20 this year is the one occurring on April 6, which will be a Thursday. So the first Sunday after April 6 is April 9, the date for Easter in Western Christianity.

Liturgical Calendar

Once Easter is dated, then the liturgical calendar for Holy Week places other observances relative to that Sunday. The Lenten season invites Christians to fast forty days in commemoration of Jesus’s forty-day sojourn in the wilderness; because Sundays are excluded from this Lenten fast, the Lenten season begins 46 days before Easter on a Wednesday, what traditionally is known as “Ash Wednesday.” The Lenten fast is observed differently depending on Christian tradition. Most Christians who observe Lent make a sacrifice of some pleasurable thing for the forty fast-days as a preparation for Easter.

Holy Week typically begins with Palm Sunday, the last Sunday before Easter, though some traditions stretch it one extra day to include the day before Palm Sunday, what’s called “Lazarus Saturday” to mark when Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead. The days of Holy Week correspond to events recounted in the Four Gospels about the final week of Jesus’s life:

- Palm Sunday—Jesus entering Jerusalem to the laying of palm leaves and shouts of Hosanna

- Holy Monday—Jesus cleansing the temple

- Holy Tuesday—Jesus teaching in the temple

- Spy Wednesday—Jesus’s anointing at Bethany; Judas’s betrayal of Jesus

- Maundy Thursday—Last Supper; Jesus in Gethsemane; Jesus’s arrest

- Good Friday—Jesus’s scourging and crucifixion; Jesus’s death and entombment

- Holy Saturday—Jesus in the realm of the dead

- Easter Sunday—Jesus’s resurrection

Celebrations and Traditions

Some years ago, I was asked to give a lesson on Holy Week and the many traditions Christians observe throughout the world. We discussed ways Latter-day Saints might join in these kinds of celebrations and I compiled all of our notes into a handout. I’ll post it here, in case you’re interested:

Easter Season Celebrations And Traditions306KB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload

In the meantime, have a most uplifting and wonderful Easter!